Stow Wengenroth was once called: “America’s greatest artist working in black and white” by the American realist painter Andrew Wyeth. He is generally considered to be one of the finest American lithographers of the 20th Century. Born in Brooklyn, New York on July 25, 1906 to Frederick Wengenroth , an architect, and Isabelle Stow, a textile designer, he studied at the Art Students League in 1923 with George Bridgman, then at the Grand Central School of Art with Wyman Adams. During the summers of the 1920’s, he went to Woodstock, New York, to work with John Carlson or to Eastport, Maine to work with George Ennis. It was Ennis who encouraged him to go into lithography.

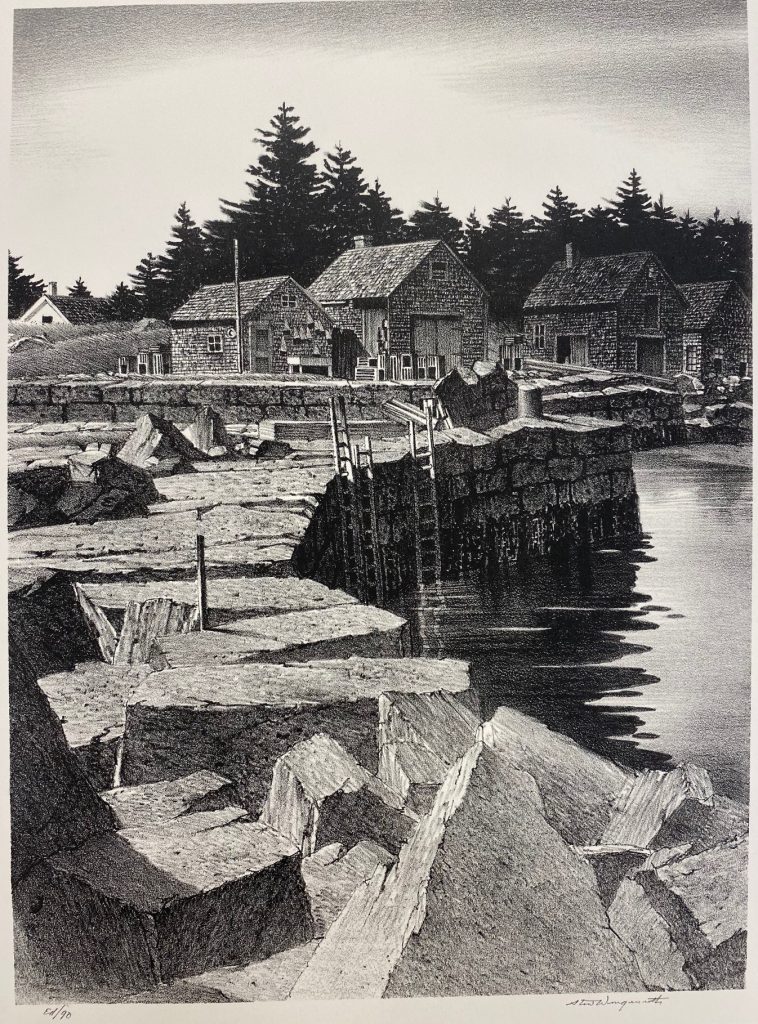

Wengenroth produced his first lithograph in February of 1931 – “Fish Wharf, Eastport, Maine.” By the end of 1931, he had made 22 other lithographs of scenes in Eastport. He kept up this pace for the rest of his life. By the time he passed away in 1978, he had produced 369 lithographs. His artistic work ethic was second to none. And, most importantly, the quality of his work was not sacrificed for quantity.

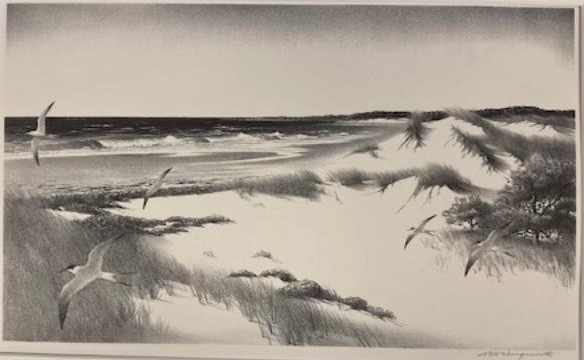

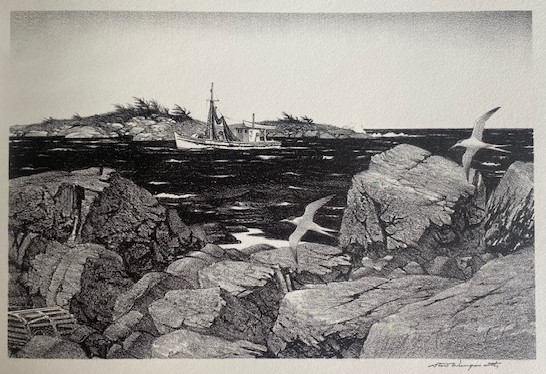

Wengenroth is well known for his lithographs of New England (particularly Maine), New York City and Long Island. He spent many summers in Maine where he found the inspiration for most of his prints. Once he found a suitable scene, he would draw it using a drybrush technique. He found that this provided the same texture that he sought in his finished lithographs. He would then redraw the image on tracing paper with a soft lead pencil. This tracing was taped to the stone (face down) and gone over with a hard, sharp pencil. Thus the softer lines were transferred to the stone and served as a guide for shading with the lithograph crayon.

An important element in any good print is the printer who transfers the artist’s image from the stone to paper. Wengenroth was fortunate in that he found George C. Miller – possibly the best printer of lithographs in the 20th Century. In the early 1930’s Wengenroth lived in Brooklyn. Miller’s studio was in Manhattan. When Wengenroth had created an image that he felt was suitable, he would walk from his home to Miller’s studio and pick up a lithographic stone. Given Wengenroth’s level of productivity and the fact that these stones weighed 75 to 90 pounds, it did not take long for him to decide to move his studio into Manhattan.

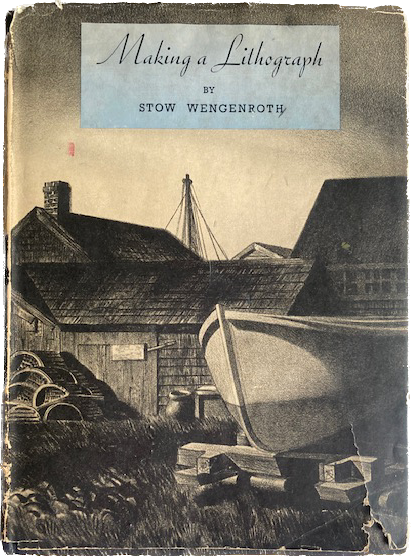

Wengenroth’s lithographs were immediately recognized as exceptional art. His popularity grew so quickly that by 1936, he was asked to write a book on lithography as part of the “How to do it” Series produced by Studio Publications. This extremely popular series included such titles as “Making an Etching” by Levon West, “Wood-Engraving and Woodcuts” by Claire Leighton and “Making a Photograph” by Ansel Adams. Wengenroth’s book was the 11th in the series.

“Making a Lithograph” remains one of the finest books ever written on this art form. It is clear, detailed and comprehensive. The process of making a lithograph is complicated and not intuitively understood. It is based on the concept that oil and water do not mix. It involves limestone slabs, pencils, tracing paper, crayons, gum Arabic, turpentine, ink, paper and a press. But with the book’s combination of Wengenroth’s outstanding text and really good pictures, it all makes sense. Many people have successfully followed it over the years. In fact, I gave my first copy to a young artist whose graphite drawings are very reminiscent of Wengenroth’s lithographs in the hope that he would take up lithography.

One might ask – “Why use tracing paper?” Of course, the answer is that the image on the stone is the reverse of the printed image. By drawing the image on the tracing paper in soft pencil, attaching it to the stone and then going over it in hard pencil, one is able to obtain a rough outline in the proper configuration.

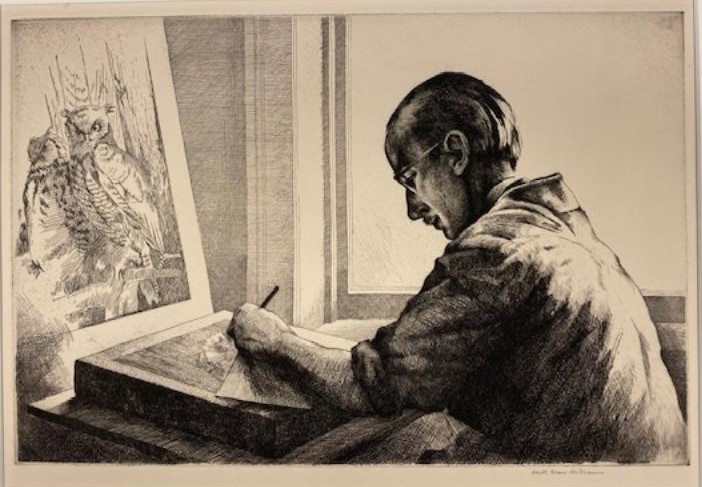

Some artists don’t do this. They just create the image on the stone (or plate) as they see it. Most of the time it does not make any difference. The scene is the same. It is just in reverse. But sometimes it does matter. A case in point is the wonderful etching at the start of this post of Stow Wengenroth done by Keith Shaw Williams. I have owned this etching for many years and always assumed Wengenroth was left-handed. As I was doing research for this blog post, I reread Wengenroth’s book on lithography. There is a similar photograph of him working on a stone for a lithograph. He was right handed.

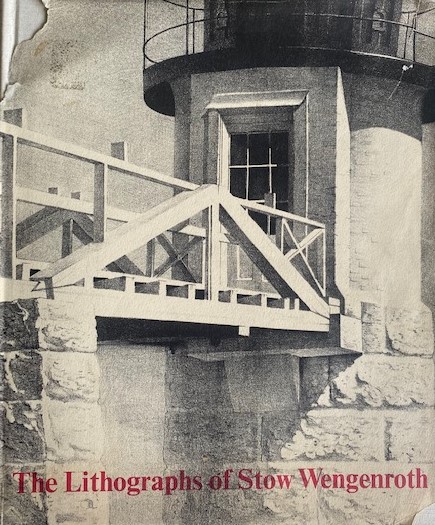

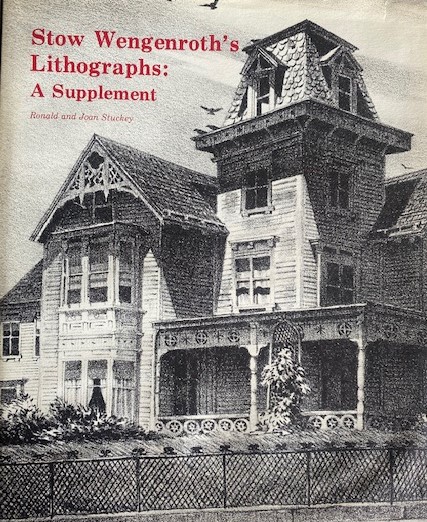

An important element in maintaining a long-lasting artistic reputation is a “catalogue raisonne” of the artist’s works. It lists all of the known pieces. The best ones also faithfully reproduce each one. Wengenroth was very fortunate to have an outstanding one written by Ronald and Joan Stuckey. It was published in 1974 by the Boston Public Library in conjunction with Barre Publishers.

The book divides Stengenroth’s art into three distinct periods: The “Early Years” (1931-1935), the “Middle Years” (1936-1951) and the “Later Years” (1952-1972). A “Supplement” to the Catalogue Raisonne was written by the Stuckeys in 1982 (Published by Black Oak Publishers) covering Stengenroth’s last 25 lithographs.

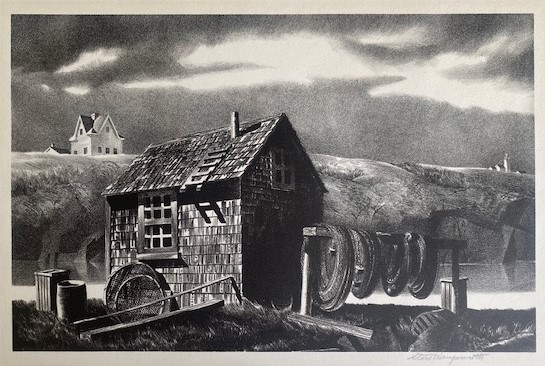

Stengenroth’s early works have a darker, more somber tone. The lithograph “Long Cove” is typical of the period. Great composition, attention to detail and precision of execution but just not very much light. Stengenroth’s works were immediately popular and sold well.

In 1936, Wengenroth had another turning point in his life. He met and married a widow by the name of Edith Flack Ackley. She had a daughter by the name of Telka. Ackley was also an artist. While she worked in painting, she is most remembered for her dolls and books. She was the author of several books including “Marionettes: Easy to Make! Fun to Use!” and “Dolls to Make for Fun and Profit.” Later in his life, Wengenroth stated that his wife was the most influential person in his work. She was an extra pair of eyes on every lithograph, she understood the creative struggle, and shared his love of art and nature.

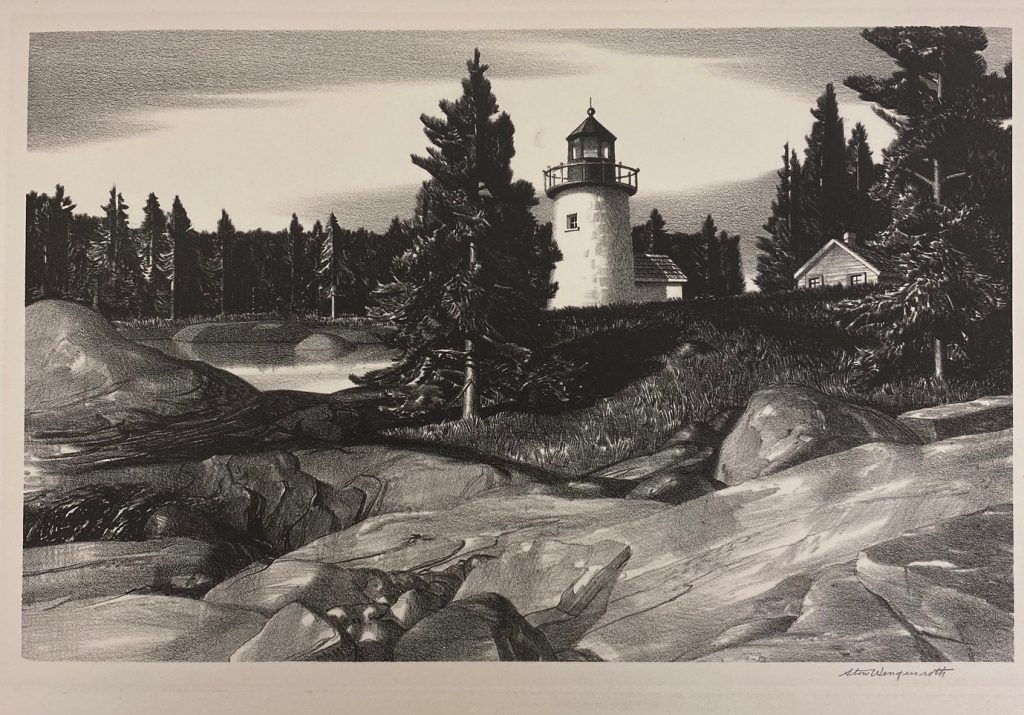

Also in the late 1930’s he started to incorporate more “light” in his lithographs. As his style developed he was able to emphasize the contrasts of his subjects. His vibrant skies, white lighthouses, white surf and white sand all contributed to works. The result was and is very appealing and one of the reasons for his almost universal popularity. His Inlet Light is a great example.

Wengenroth was asked on several occasions to create prints for the Prairie Print Makers associate members. These were called Presentation Prints. Each of the Prairie Print Maker Presentation Prints was sent in a portfolio with an essay from a leading art critic or fellow artist. The “New England Village” 1940 Presentation Print version was written by Ernest W. Watson . In my opinion, it is one of the best pieces describing Stow Wengenroth as an artist and of the lithographs he created.

“It would be easy to copy the jargon of innumerable critics who have written columns (almost wholly in praise), describing the unique genius of the artist and the impressive qualities of his work. But insofar as it is possible – or necessary – to analyze and account for Wengenroth’s creative power, it should be sufficient to remember: first, that this artist possesses – as do all true artists – a vision that extends beyond the surface appearances of nature: no artist ever saw nature as does Wengenroth – no artist ever will. Wengenroth is as definitely Wengenroth as Corot is Corot; as Cezanne is Cezanne. He has not borrowed Cezanne’s spectacles, nor Tom Benton’s, nor those of Ennis, his former instructor. He has his own impressions, his own interpretations. He goes his own independent way regardless of the “styles” set by other artists.”

“In the second place, Wengenroth’s craftsmanship matches his vision. His mastery of composition, his fine sense of values, his superb draftsmanship enable him to share his vision with others who are sensitive enough to perceive it in those lithographs of fishermen’s shacks, wharfs, lighthouses, and ships that he loves to portray.”

“Wengenroth has a sort of mystical power of investing material things with strange significance. When he draws a wheelbarrow, a bucket, a woodshed, these inconsequential things somehow become important: they cast a spell. No one can tell how he does it. But only a true artist can do such things.”

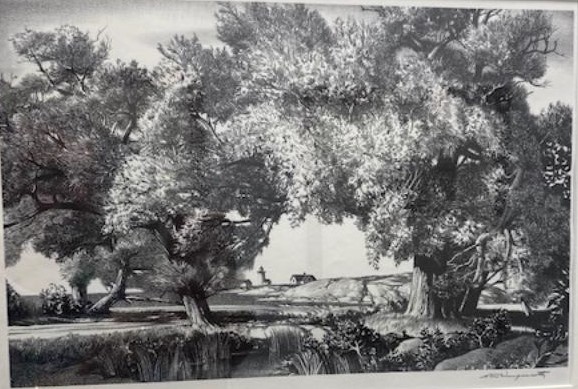

Another great example is his Cape Ann Willows.

“Cape Ann Willows” was commissioned by the Society of Print Connoisseurs. Wengenroth wrote an essay to accompany the print. It does a great job of conveying what he was trying to achieve with this print and applies to most of prints that he did in his career.

“If a little of the pleasure I got from being near these willows in that beautiful spot and if a little of the exhilaration I felt by being out-of-doors on those early September days are conveyed to those who behold the print, I shall have accomplished something for them. It the season of quiet, of serenity and repose. . . that time of stillness, of arrested animations. Such days are dramatic in their restraint, but they live long in our memories. . . The print will serve its purpose well if it conveys to those who see it something of the enthusiasm and pleasure that went into its making.”

The Secretary of the Prairie Print Makers at this time was James Swann. This letter is from the James Swann Archives at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art.

“December 16, 1957

Dear Stow:

The three parcels of prints of “The Far Shore” have reached me and I have mailed out most of the prints to the paid up members. I am holding two that just came in from San Antonio, Texas as I hate to put them in the mails at this time. I wrote these members that the prints would be mailed after Christmas.

I enclose herewith the Prairie Print Makers check in the amount of $150 for the publication prints and thank you again for making us such a fine print.”

Swann is referring to “Associate Members” of the Prairie Print Makers. These were individuals who paid $5.00 per year for their membership. In return, they received a “Presentation Print” and the knowledge that they were supporting the artists involved in making prints. It looks like the cost per print was $0.75. Mailing was probably another $0.25 for a total of $1.00 – netting $4.00 for the group. This money was used to pay Swann’s “salary” and to cover the costs of PPM art shows.

Obviously, Swann needed to make some additional income to live in the city of Chicago. Besides selling his own prints, he had an “art gallery” of prints in his basement to sell to the public. At one point, he had over 20,000 prints and represented many of the best print makers. One of his artists was Stow Wengenroth. Swann’s letter continues . . .

“The man who bought the five lithographs some time ago has just this minute left with them . . . And I enclose also my check for the following:

Season’s End. $18.00

Sanctuary. $20.00

Downy Woodpeckers. $15.00

Conflict. $20.00

Hidden Grove. $6.00

Winter. $20.00

Total $99.00

Less 1/3. $33.00

My check. $66.00

I hope that you have a nice Christmas. . . I leave on Wednesday morning for Texas . . . To be gone until the 28th of December.

Very Sincerely, Jimmie”

This letter gives us some insight into the lives of print artists. Both Wengenroth and Swann lived entirely off of their art income. Although, the 1950’s were much better for artists than the 30’s, it was not a lucrative career. In fact, except for a few very successful artists, it remains so today.

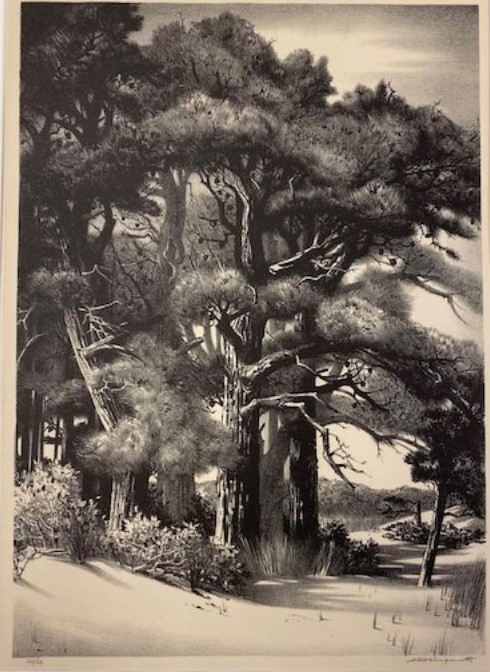

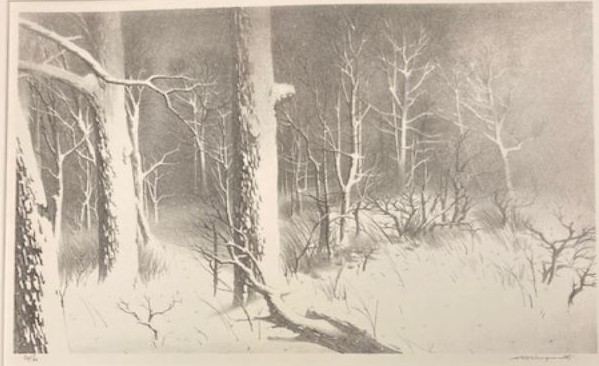

One of the prints sold by Swann was “Winter”:

Wengenroth received many honors and awards. He was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1938. This was a prestigious honor and confirmation of his artistic talents from his peers. To become a member, new nominees had to be voted in by a majority of existing members. James Swann applied for membership in 1957. Here is the letter Wengenroth sent to Swann after his vote:

“Dear Jim

Sure hope you make the Academy. I had the pleasure of sending in my ballot a few days ago with a great big check in the yes column after your name.

Thank you for your note. The show is going very well – better than I would have hoped for.

Was amused at the page from the catalogue you sent. I have seen my name spelled many strange ways but this certainly shows the most originality! Too bad I was not more attentive in school during penmanship class.

Cordially, Stow W.”

(Author’s note: I agree with W.. He should have worked a little harder on his penmanship in school.)

Swann was also supported by such notables as Gene Kloss, Robert von Neumann, Reynold Weidenaar, James Havens and Luigi Lucioni. Unfortunately, he was not elected to the Academy.

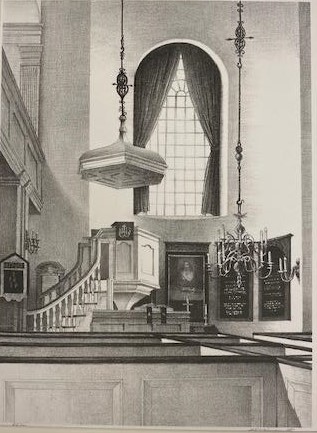

Wengenroth continued to produce very fine etchings well past normal “retirement age.” Two of my favorites are Flat Rock Cove that he created when he was 65 and Old North Church when he was 70.

Throughout his career Wengenroth produced 369 different lithographs and many more drybrush drawings. After his first wife passed away in 1970, he took up watercolor. He had not worked in watercolor since the 1920’s and produced a remarkable but small body of watercolors. Most were not signed by the artist.

He died on January 22, 1978 in Gloucester, Massachusetts.

Leave a Reply