By Jim Rosenthal

John Taylor Arms was a masterful etcher. His detailed works covered a wide range of subjects from French Gothic cathedrals to Northern Italian Renaissance buildings to US fighting ships. But he was much more than that. He had a profound influence on prints, printmaking and the associations that supported and promoted printmakers. Besides that – he was a really nice guy.

When I was researching for my blog post on John W. Winkler, the name John Taylor Arms kept coming up. Arms and Winkler spent several years together in France in the early 1920’s. During that time they developed a strong friendship that would last for over 30 years. They shared a common bond in their art, but Winkler went through many years where he was very much of a recluse and suffered from depression. He wrote very few letters. He did not answer his phone. He often didn’t even answer his door. Many of his friends gave up on him – but not John Taylor Arms. Arms kept up his sustaining affirmation of Winkler’s etching and his caring for his friend. Eventually this devotion ensured his survival, as Winkler was quick to acknowledge in later years. (for more details on John Winkler see https://www.inpraiseofprints.com/john-w-winkler-and-elizabeth-ginno-winkler-master-etchers-a-christmas-card-story/)

So my question became: “Was Arms’ approach to Winkler unique or was it part of a pattern of good deeds of a good man?” Further research confirmed that it was the later. John Taylor Arms devoted his life to his family, his friends and his art. Just as importantly, he spent literally thousands of hours working to develop artist associations and their artist members. He was encouraging, inclusive and open-minded. As a result, he not only kept alive the traditions of representational art, he also paved the way for emergence of and transition to modern printmaking.

John Taylor Arms was born in Washington, D.C. on April 19, 1887. He started his education at Princeton studying law. By 1905 he transferred to MIT to study architecture and after graduation in 1912 went into this profession. By 1914 he had made partner in his firm. He married Dorothy Noyes in 1913. She gave him an “etching set” for a Christmas present that year.

He created and sold his first etchings by 1916. After serving in the Navy during WWI, he gave up his architectural career and went into etching full time. He also joined the Brooklyn Society of Etchers thus beginning his life long connection with print societies. By 1920 he had been elected President of this group.

Dorothy Noyes Arms was a big part of what made John Taylor Arms the man that he was. She not only provided the inspiration for his start in etching, she was also his companion, co-worker, co-traveler, writer, spouse and best friend. She was with him every step of the way on all of his trips abroad. He etched and she wrote. It was a good team.

To give an idea of her writing skill and style, let me quote her from a book titled The Romance of Fine Prints edited by Alfred Fowler and printed by The Print Society in 1938:

“The title, ‘The Romance of Fine Prints’ is so completely imagination-provoking that it becomes a question not of how it can be interpreted, but of what can be omitted in order to hold the story within the compass of a reasonable number of pages.

For us the romance of prints has two separate and distinct manifestations – the collecting and the making of prints. In one there is an aura of association: this print was acquired under certain conditions; that one represents the work of a dear friend; still another speaks with a voice from the past, telling the tale of survival through the ages which is a miracle and a romance in itself. In the other there are all the personal sides; the reasons for choosing a subject, the small or the larger events surrounding the making of it, the ‘feeling’ of a place, the little adventures connected with it, or the thousand and one things which make that print an individual one in our memories. This, then, is the personal point of view we wish to stress.”

Dorothy Arms could create beautiful, poetic prose. It was a perfect complement to her husbands etchings. Their books included Churches of France and Hill Towns and Cities of Northern Italy. The etchings in these two books represent some of JTA’s finest work. His incredibly detailed representations of Gothic Cathedrals were a tribute to his appreciation for Gothic architecture. He considered it to be the closest man has come to physical perfection and he did everything he could to try to show this beauty in his etchings.

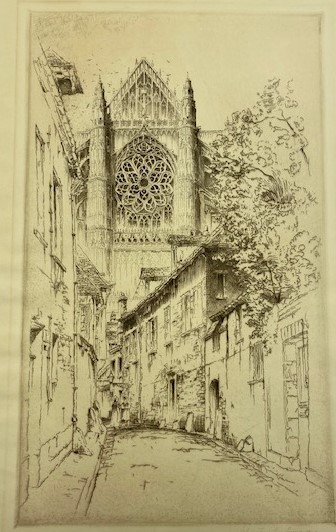

1925

John Taylor Arms

Included in Churches of France book by Dorothy and John Taylor Arms

12″X7″ image

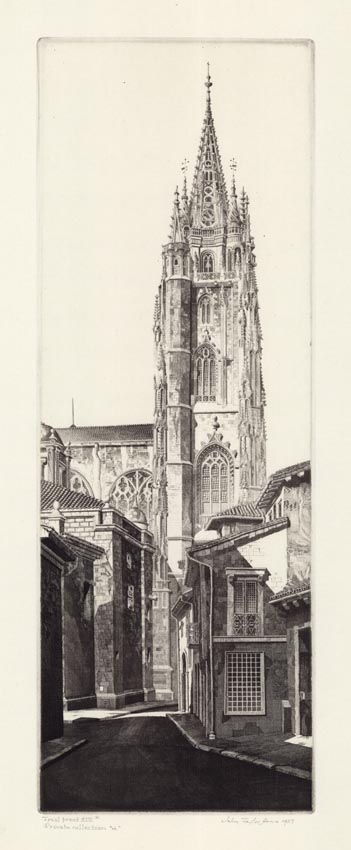

1937

by John Taylor Arms

12 1/4″ X 4 3/8″

Arms produced over 400 etchings in his artistic career. Other major series included the Gable Series, the Aquatint Series, Maine Series and New York Series. In 1928 one of his prints, Saint Germain L’Auxerrois, Paris, was selected to be the Presentation Print for the Chicago Society of Etchers.

1928 Presentation Print – Chicago Society of Etchers

John Taylor Arms

Image 9 7/8″ X 5″

In the mid-1900’s miniature prints became an important part of the art world. Both the Chicago Society of Etchers and the American Society of Etchers included them in their annual shows. Arms immediately saw the potential of this art form and embraced it whole heartedly. He also had his standards. “A miniature must not be made just to fit in the size category. It needed to involve the full skills and artistic talent of the artist to create something of artist value which must be on a scale commensurate with the dimensions of the plate.” (from the Miniature Print Society introductory brochure)

Arms, in his usual 100% involvement way, created many miniature etchings. It fit his precision oriented style. The miniatures he did were on the same level as his larger etchings. He did a total of 41 miniatures in this series.

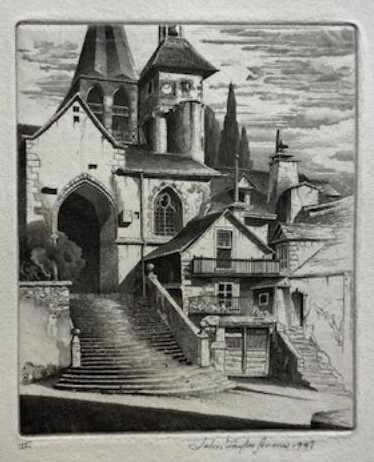

1947

John Taylor Arms

Part of the Miniature Church Series

Image 2 7/8″ X 2 1/2″

Like many artists of his era (and of today) John Taylor Arms and Dorothy Arms enjoyed sending Christmas Cards. His 1926 card gives a good idea of his interpretations of Gothic art. It was one of his first in a series of cards that went on for 17 years.

Dorothy and John Taylor Arms

1926

Image 6 1/8″ X 3 9/16″

Sometimes his emphasis on fairness and impartiality in judging put him in some unusual situations. For example, for many years he served on the committee for the Pennell Fund that selected prints to be purchased for the Library of Congress. Joseph Pennell was a long time friend of JTA and a major force in the development of etchers and etching in the early 1900’s. An avid disciple of James Whistler, Pennell was well known for his prodigious and excellent etching production and his strong opinions on every aspect of etching. In his book Etchers and Etchings he expresses those opinions on everything from grounding a plate to matting and framing an etching. He also gives his thoughts on the subject of “color etchings.”

“I have said little or nothing about this form of publishing etchings, because it is merely a method of printing; though it has grown into a uselessly elaborate way of getting a simple but inartistic result and it has become a commercial commodity.

The person who demands color and the artist who supplies it in print are totally incapable of appreciating or understanding an etching.”

As we have seen, Arms was not so inflexible and he accepted and encouraged the creativity, resourcefulness and talents of other artists. The committee had recently included color prints in their selection. In a letter to Katherine Ely Ingraham he wrote:

“I agree with you that Joe Pennell would certainly turn over in his grave at the idea of a color etching being included in his sanctified collection, but, if that is true, then the old man is doing a veritable flip-flop these past years because of my being one of those to spend his money on prints!”

(Quote from James Watrous A Century of American Printmaking – 1880-1980, page 81)

Arms was involved with print organizations for much of his career. He was a participant in the early shows of the Brooklyn Society of Etchers and served as its President in 1920. Originally, this organization focused on membership in the Brooklyn/New York area. As it expanded to include artist members from throughout the United States, it changed it’s name to the Society of American Etchers. He was the President of this organization for many years as well.

The American Society of Etchers, the Chicago Society of Etchers and other regional etching societies followed the same general model. They had active artist members who were “approved” by current members. All also had Associate members who were non-artists. These Associate members paid an annual fee which entitled them to receive a “Presentation Print” selected by a committee of artist members. The fee was $5.00 which more than covered the cost of the producing the print and the “prize” for the artist who created it. The balance went into the Treasury of the organization to cover other expenses.

The etching societies held annual juried shows to give their members exposure to the public and to sell their prints. The Chicago Society of Etchers held theirs at the Art Institute of Chicago for many years. The Brooklyn Society of Etchers held theirs at the Brooklyn Museum. After their local showing, the exhibits of etchings travelled the country to other cities.

The etching societies also functioned to inform the public about the art of etching. The major method was through “demonstrations” put on by members to show how an etching was created from the needle work on the grounded plate to the etching of the plate in acid to the printing of the final print.

John Taylor Arms performed many demonstrations with the Society of American Etchers. Arms even went on television in 1940 to demonstrate the art of etching. The SAE also exhibited at the 1939-1940 World’s Fair in New York City. The highlight of this participation was SAE day where 39 members of the organization demonstrated ten media in both color and black and white. According to Arms, it was the largest demonstration ever held.

Apparently, a JTA demonstration was a memorable event. His friend and fellow etcher, Samuel Chamberlain, had this to say about his one hundredth demonstration –

“This is an amazing performance in which he follows all of the steps of making a plate – grounding the copper surface, needling the picture (casually drawing with both hands), biting in acid and pulling a finished proof – all in one tense sitting, while carrying on a stentorian monologue and apparently not stopping once for breath.” (from an article in Print magazine – March 1941 by Chamberlain titled “Phenomenon.”)

At the urging of Bertha Jaques, Secretary-Treasurer, of the Chicago Society of Etchers, James Swann submitted four etchings to the Society of American Etchers for inclusion in their annual show. (Bertha Jaques was the founder of the CSE and the driving force behind that organization for twenty-seven years – 1910 to 1937.) Swann’s etchings were not accepted and the “rejection letter” from Arms to Jaques provides some insight into his activities and his caring for other artists.

From John Taylor Arms, President, The Society of American Etchers

Letter dated October 23, 1937

“Dear Bertha Jaques:

What a week it has been! Last week-end was the two day session of the jury of selection for the S. A. E. Annual and Tuesday and Wednesday were spent at Wesleyan University demonstrating etching before the students there; and at the meantime I worked night and day in my studio on the plate that I must finish in time to have David Strang print it by the first of November. There just has not been a moment when I could write even a line about James Swann’s prints.

His prints interest me very much, as I have told you, but unfortunately none was accepted for the coming Annual Exhibition. . . . The jury had to drastically reduce the number of prints in the show because of our commitment to hang 185 Swedish prints. . . . He should not feel hurt since so few of the hundreds of fine prints received could be included.. . . I have no doubt that if he will continue to send to our shows, his work will receive the recognition it deserves. . . By all means, do not let him feel discouraged.” “Most sincerely your friend, John”

(The salutation in the above letter is interesting. Arms was on a first name basis with hundreds of leading artists, museum directors, art dealers and art critics. Yet, he chose to use “Bertha Jaques” for his opening. I guess that was his 1930’s way of being friendly – but not too familiar.)

This is a short summary of the Arms letter that is a full two typed pages. Keep in mind that as President of the Society of American Etchers, he had assumed the responsibilities for the show and all of the details that went with it. He had to contact each artist to solicit the entries, receive the prints, coordinate their return or use and communicate all of these details. Yet, Arms found the time to write a personal, thoughtful letter to his friend concerning her young protege.

(This letter is from the James Swann Archives at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art. It has a hand-written note on the top from Bertha Jaques to James Swann – “please read and return sometime.”)

Due to Bertha Jaques failing health she turned over the reigns of the Chicago Society of Etchers to James Swann at the end of 1937. The next letter from Arms to Swann in the Archives is dated November 28, 1939. Arms is writing in his official title of President of the American Society of Etchers. In the letter he proposes a swap of names of Associate Members from his organization for the names and addresses of the Associate Members of the CSE. List swaps like this were fairly common. A similar exchange had taken place between the two organizations in 1933. Even though there is not a follow-up letter in the archive, it is safe to assume that the transaction took place.

John Taylor Arms was proof of the old adage – “If you want something done, give it to a busy man.” By the late 1930’s Arms had been President of one of the leading print organizations for over 15 years. So when a group of leading American printmakers decided that they needed a new organization to promote the cause of the graphic arts called the American National Committee of Engraving, their obvious choice for President was John Taylor Arms. Members included such notables as Ernest Roth, Gustave Baumann, Frank Benson, Isabel Bishop, Rockwell Kent, John Sloan and Stow Wengenroth. James Swann served as a Vice President-Secretary.

One of the first activities of this new group was an exchange exhibition with artists from Hawaii. Working with the Honolulu Academy of Arts, Arms was able to organize an exhibition tour in 1940 of “Fifty Prints from Hawaii.” Tour stops included the New York World’s Fair and museums in Tulsa, Boston, Manchester and Albany. In exchange a selection of “Fifty Prints from the Mainland” was exhibited in Hawaii.

In a letter dated May 8, 1940 from Arms to “Jimmie” Swann he discusses the logistics of the two exchanges. Swann was helping to recruit artists for the “mainland prints” and was working on possible venues in Chicago for the Hawaiian print exhibition. Arms goes on to explain that he had also organized an “Exhibition of Mexican Prints” to be shown at the Fair. In addition he was making “plans for the show of British and French artists in the service” to be held in late October. These exhibitions were also scheduled to go to different cities under the auspices of the Committee.

The world changed virtually overnight. The Germans attacked France on May 10, 1940, captured Paris by the middle of June and signed an armistice on June 18th. The British Army barely escaped through Dunkirk in late May and early June of 1940.

Of course, things changed quickly in Hawaii as well. By the end of 1941, the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. The eyes of the world were no longer on prints and print exhibitions. The focus of the entire country was on winning World War II.

As it turns out the relationship between John Taylor Arms and the Honolulu Academy of Arts endures to this day. This institution has a comprehensive collection of JTA prints and organized a major exhibit of his work in 1993. As a part of the commitment to that exhibit Jennifer Saville wrote an excellent book on Arms entitled “John Taylor Arms – Plates in Perfect Beauty.” It is a thoroughly researched and well written account of Arms’ career both as an artist and as a major force in the prints world. Any fan of John Taylor Arms needs to have it in their library.

The onset of WWII created other problems for JTA as well. He had organized an Exhibition of American Prints and Drawings to be a part of the Venetian Biennial in Italy. He had coordinated this event in cooperation with the Society of American Etchers, the National Academy and the Grand Central Art Galleries. Works by over two hundred American artists were included. The exhibition opened in early June 1940 and was scheduled to run for the rest of the year. Unfortunately, Italy declared war on France and England on June 10th. By June 17th all artist participants (including James Swann) received a letter from Arms explaining that on the basis of a vote by the organizations and artists, the American prints and drawings were being withdrawn from the show. This artwork was being stored “in a safe place” in Italy by Arms’ Italian contact. It was not stated how and when (or if) the artwork was ever returned to the artists.

As mentioned above, growing the list of Associate Members was important for these art organizations because their dues were a major source of revenue. It also benefitted the Artist Members because it exposed them to a larger audience of collectors and purchasers of their prints. Associate Members were owners of businesses, lawyers, doctors and other professionals with an interest in art. Virtually all were collectors – and an avid collector seldom passes up an opportunity to purchase a good print. Thus, adding to the Associate Member list benefitted all parties.

However, not everyone saw it that way. In 1946 James Swann, Secretary-Treasurer of the Chicago Society of Etchers, traded the CSE list with Albert Fowler who ran both the Woodcut Society and the Miniature Print Society. Some CSE Board Members did not approve and they forced Swann to resign his position. Within a year, Swann was made Secretary-Treasurer of the Prairie Print Makers.

Arms knew better than anyone what it was like to run a print society. In a letter to Swann dated May 26, 1948 he expressed his thoughts:

“I have wanted to write you chiefly to say that I dunno where your Society will find another such devoted servant! Indeed I don’t see how you can be replaced for people who give so much of themselves to such a cause are so rare.”

He closed with:

“All the luck in the world in your New Capacity, Jimmie!”

Arms was always first and foremost an etcher (although he did create a few lithographs). His emphasis on clean lines and sharp detail were the driving force in his work. Some of his etchings took over 1,000 hours to complete. He was constantly looking for ways to provide the precision he wanted in his work. Typical etching needles were not sufficient. He found the answer in diamond tipped phonographic needles. He often worked with a magnifying glass to ensure accuracy. The right tools, abundant patience and artistic skill created the etchings that have stood the test of time to this day. Arms’ work has never lost it’s popularity.

Although he was a traditional representational artist, once he understood that art had to evolve, he fought for the rights and the recognition of other artists who did not share his style. He thought many of the “modern” artists to be superficial. They “tried to be clever” rather than technically sound. He freely admitted that he did not “understand” much of what was being created. But he did understand that it was their right to create it and to be recognized for it.

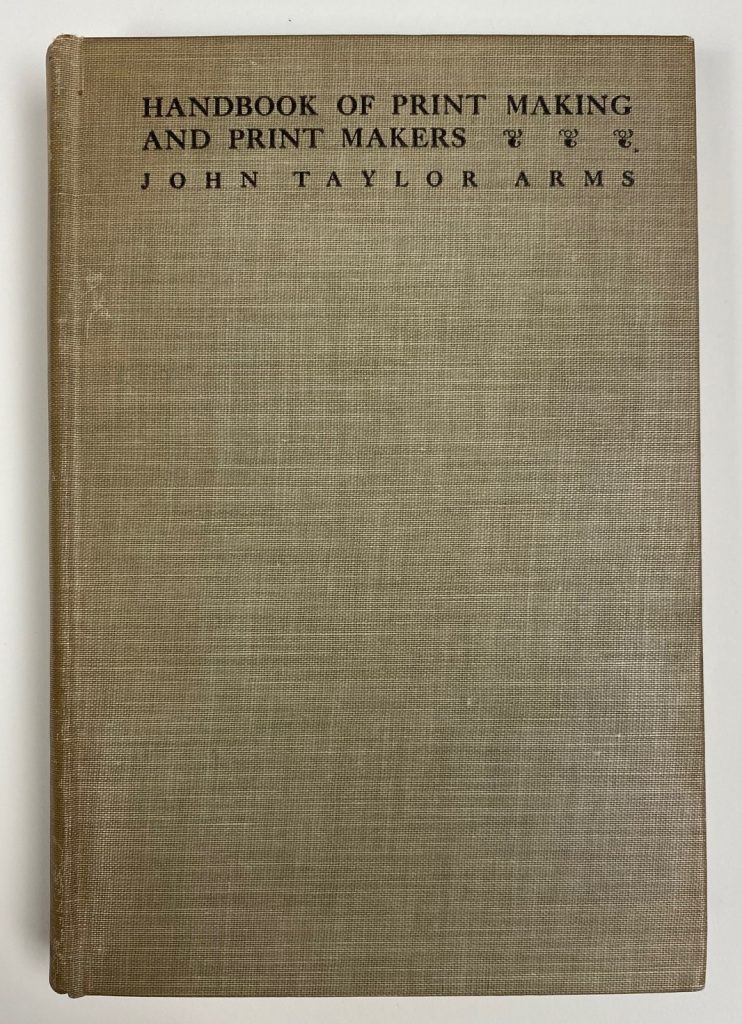

Early on he was focused on encouraging the understanding and appreciation of all types of prints. To this end he wrote a book titled Handbook of Print Making and Print Makers in 1934. The book clearly and concisely describes the techniques of etching, dry-point, line-engraving, woodcut, wood engraving, mezzotint, color-printing and lithography. Each chapter then provides a history and details about some of the masters of each technique.

JTA did not consider himself an expert in all methods of making prints so he enlisted the help of several fellow artists. For woodcuts and wood engraving his choice was J. J. Lankes. For lithography he chose Bolton Brown. Both were major forces in popularizing their respective specialties.

The book is well written and easy to understand. It became a valuable reference work for those who appreciate fine prints.

He also understood that art societies needed to adapt to a changing world. Unlike the Chicago Society of Etchers who doggedly insisted that they could only include intaglio art (etchings, drypoints, aquatints, mezzotints) in their exhibitions, Arms felt it was necessary to include a broad range of printmakers. Consequently, in 1947 the Society of American Etchers changed its name to the Society of American Etchers, Gravers, Lithographers and Woodcutters. After 5 years of living with this tongue-twister of a name, the organization made another change to the Society of American Graphic Artists (SAGA) – the name it goes by today.

In a letter to Rockwell Kent dated January 21, 1937 he lays out what he was trying to achieve:

“real exhibitions of real American prints with no prejudice in favor of any ‘school’ or ‘tendency’ but with every effort made to have it contain an example of the work of every sincere and significant American print maker, irrespective of whether he calls himself ‘modern’, ‘conservative’ or anything else.”

This cooperative and collegial attitude won Arms many friends in the artistic community. How could you not like someone who is smart, supportive, accepting and positive? Plus, there was no question about the level of his personal artistic talent. No matter what your preference in art, you cannot help but appreciate and admire works by John Taylor Arms.

Being the head of an arts society is not an easy job. It requires a tremendous amount of time and effort. One has to be an administrator, a politician, a counselor and much more. And Arms did this for over 30 years. The question is why. How could he do this? For John Taylor Arms (and others like him) that is not the question. The question is: How could he NOT do this? To Arms it was enjoyable. It was never tedium or work. It was people – artists, art dealers, collectors, museum directors and the man on the street. It was seeing others succeed. It was making things happen – whether it was an exhibition, a newsletter or a meeting. And it was all for a cause he believed in – the creation, enjoyment and appreciation of the art of printmaking and the resulting prints. I cannot find any reference to Arms ever receiving a dime in compensation for his countless hours of work. The experience of successfully doing the work was enough for him. To some giving is receiving. Arms was such a man.

John Taylor Arms died in 1953. During his lifetime he received countless awards recognizing his art and his contributions to the art of printmaking. His work is represented in museums around the world and is still very popular today.

After his passing, the accolades rolled in.

This from John Winkler:

“John Taylor Arms will live on and on and future generations centuries from now will marvel at his work. . . . As a friend and as a man he fully matched his superb work.”

The popular and well known etcher, Roi Partridge, had this to say:

“No one in this country, except possibly Bertha E. Jaques, has done as much for etchers and etching as Arms did. He was outstanding as a kindly, helpful man who reached out beyond himself to touch and influence the lives of others.”

Albert Reese of Kennedy Galleries wrote:

“Arms has probably done more than anyone else to keep printmaking a living and vital force in American art.”

Representative of the feelings of many artists of this era is a letter from Claire Leighton to James Swann dated November 12, 1954. In the letter she apologized for not sending some miniatures for an exhibition to Swann and closed with this:

“I don’t know why life has seemed so cluttered of late, but it has. One reason is that I have been helping Dorothy Arms in disposing of John’s fantastic supply of material. I have got it, just now, in the store room. Goodness, how that man hoarded. There is enough paper to keep twenty artists supplied for ten lifetimes. I have, now, to try to get in touch with needy artists. It’s a stupendous job, but I loved that man so much that I cannot resent the effort.”

That was and is his legacy. He was a superb artist. But he was a person who spent his career helping others. Many “loved the man” because he made a difference to improve the art world and their art. In short, he was a “nice guy” and he finished first.

Very nice read. I have noticed that there are many copies of his etchings for sale on the market that I would guess where copied from a original plate. At home I have an original drawing of the Rialto Bridge in Venice dated 1929 that was purchased a long time ago in New York from the Kennedy and CO. Are his original drawings more rare as compared to an etching?

Generally, original drawings are more valuable than etching prints. However, it depends on condition, subject matter, artistic appeal and having the right buyer. The fact that your drawing came from Kennedy and Company is a big plus. This was and is a leading gallery and they represented John Taylor Arms so the authenticity is assured. And, yes, a drawing is more rare since there is only one while there may be 100 or more etching prints made from one plate.

Thanks so much for collecting so much interesting information and wonderful stories about JTA! I am a huge fan of printmakers especially Arms and Martin Lewis, and Stow Wengenroth, my artistic holy trinity.

Glad you enjoyed the article. I also enjoy Arms’ work, but it is his contribution to the print world that captures my interest. He was a tireless advocate for prints and printmakers and an excellent role model for any endeavor. I also enjoy Lewis and Wengenroth. Wengenroth is on my short list for future articles. I love his lithographs and his approach to his art.