One of the most interesting artists of the first half of the Twentieth Century was Cyrus Leroy Baldridge. His life story rivals that of any adventurer of any era. It is ironic, but fitting, that one of his most popular books was the illustrated “Adventures of Marco Polo.” He was a “Marco Polo” of his day – perhaps with a bit of Ernest Hemingway thrown in.

Baldridge was born in 1889 to a single mother. He spent much of his early life on the road as his mother practiced her trade of selling cookware called “Fire Clay” door to door. By the time he was 12 his mother had moved to Chicago and found a job working in a retail store.

She felt that her boy had artistic talent and she was determined to see that he obtained the proper training. Somehow she persuaded the well-known artist and teacher, Frank Holme, to take “Roy” into his class at the School of Illustration “on trial for a week.” He passed the trial and soon he was participating in classes with other students three times his age.

On one notable occasion Holme was critiquing the drawings of all of the students. The last piece he showed to the class was on a small piece of ragged grey paper. Some of the class thought it was funny and laughed. Holme thought otherwise and said: “You folks don’t seem to realize that this is the best of the lot. Why? Because it is simple. The story is told with a dozen lines. There is not one unnecessary touch.” The drawing on the ragged gray paper was Roy’s.

When he received his drawing back from Holme, it had the notation: “Roy, always be brief! Say what you have to say with a few bold strokes. Never forget!” And the lesson stayed with him for the rest of his life.

The Baldridges stayed in Chicago a few more years and he continued his classes with Frank Holme. They moved to Kewanee, Illinois when his mother married the hotel owner in that town. Things settled down for him for awhile and he lived a comfortable life in this small town.

He had done moderately well in school and was determined to go to College. He showed up at the University of Chicago with the $800 he had saved, no scholarship, no room and no friends. He graduated four years later as a member of the Senior Honor Society and “Head Marshal” of his class. His entry in the school yearbook was “thirteen lines of honors he had received.” He never received a scholarship – but worked his way through school starting as a waiter in the school dining hall and finishing using his artistic talents for just about every sign put up at the University.

After graduating he joined the famed Chicago “Palette and Chisel” Club. He was an active member and was put in charge of the Junior Club whose purpose was to instruct the “street urchins” in the neighborhood on the finer points of art. This only occupied part of his time so he enlisted as a cavalryman in the Illinois National Guard. He learned to ride a horse and some military discipline. The horse skills would come in handy in his summer job as a ranch hand at the 6666 Ranch in the Panhandle of Texas.

Shortly after returning to Chicago from his Texas experience in 1914, war broke out in Europe. Roy Baldridge was eager to go to Europe to be near the action since many people thought “The War will be over by Christmas.” He booked a place on a steamer headed for Belgium and arrived in the middle of the war zone. His objective was to report the War through his drawings and sketches. The United States was neutral at this point so both sides wanted to include Americans in their side of the story. Baldridge wandered through Belgium and eventually received a pass from the Germans to move anywhere in their control. But with little money – and no plan to make any – he had to return to the United States.

Shortly after his return, Pancho Villa crossed the US-Mexico border to attack a US town and the National Guard was activated. This included the Illinois Cavalry. Baldridge was sent back to Texas. This time as a Corporal in the US Army under the command of General Pershing. Baldridge talks of work “building trenches” but his unit saw no action.

By 1917 he was back in Europe. This time he connected with the French Army and was given wide latitude to draw anything that he found important. After a few months, the United States entered the War and he joined the staff of the fledgling US Army publication – Stars and Stripes. This weekly newspaper became one of the most widely read of the early 20th Century. Regular distribution was 550,000 to the US troops. There were 50,000 US subscribers and over 150,000 copies of each issue were sent home by US troops. The team that worked on Stars and Stripes became leaders in the world of print news in the US. One reporter, Harold Ross, founded the New Yorker. Another, John Winterich, started the Colophon and was a consulting editor for the Saturday Review of Literature. Cyrus Leroy Baldridge became a household name and few people in America had not seen and admired his drawings, sketches and tributes to the American soldier. I was there! – his book of this material was a best seller.

Baldridge’s illustrations were not of battle scenes or famous Generals. They were illustrations of common soldiers who were displayed with a sensitivity and humanity that endeared him to all. Like many young men who witnessed “The Great War”, Baldridge went away with a clear understanding of the horrors of modern conflict. There was no chivalry in the bloodshed and suffering of the soldiers from all Armies in the War. This experience would have a profound effect on him for the rest of his life.

Leroy Baldridge’s Depiction of the soldier’s reaction to Armistice Day

Leroy Baldridge’s Depiction of the soldier’s reaction to Armistice Day

After the Armistice ending WWI, Baldridge remained in Paris where he enrolled in the Academie Julien. His next door neighbor was a tall, attractive publicist for the American Red Cross by the name of Caroline Singer. Roy and Caroline enjoyed their time together for the next few months until the wind-down of the American military presence in France came to an end. They boarded a troop ship for New York in 1919.

After a short time in New York, Baldridge’s wanderlust took over again so he set off for the Orient visiting China, Korea and Japan. And when Baldridge travelled, he was not your average tourist. He lived with the native people, ate with them, slept in their houses and got to know their families. He was also drawing what he saw and experienced. The sketchbook was his constant companion.

After the better part of a year on the road, he returned to New York. Some friends invited him to dinner one night and there just happened to be an old acquaintance at his host’s house – Caroline Singer. They reunited, married and were never separated for the rest of their lives.

Caroline Singer

Caroline shared Roy’s love for travel and adventure. They might be able to go for a year or two in New York where Roy became one of the leading illustrators in the country, but eventually the urge to be on the road would take over. They would pack, seal up their apartment and be on the next steamer to who knows where. Africa, the Orient, the Middle East were all frequent destinations. One time they spent months in Africa going from village to village on bicycles. Roy with his sketchbook and Caroline with her note pad.

As it turns out, Caroline was a superb writer and enjoyed her craft as much as Roy enjoyed his. Caroline wrote several books and many articles about their travels. Roy did the illustrations. Their African trips were in their book – White Africans and Black. Their adventures in the Middle East and Asia are included in the books – Turn to the East and Half the World is Isfahan. Many of these adventures are also described in Baldridge’s autobiography – Time and Chance.

The books sold well. In addition, Roy was in demand for his book and article illustrations. At that time most books were illustrated with line drawings. His work was featured in the above mentioned Marco Polo as well as the children’s classics – Lassie Come Home and Hans Brinker and the Silver Skates.

While in the United States, Baldridge became involved in the American Legion – specifically the Willard Straight Post. This post was vehemently anti-war and was filled with ex-soldiers who experienced many of the same horrors of the trenches of World War I. Part of his activity at the Post involved his writing a pamphlet entitled – “Americanism: What is it?” The pamphlet was widely distributed throughout the country and it’s main theme can be summarized through this passage – “True American Patriotism is a one hundred percent belief in Democracy, Justice and Liberty. To preserve this the patriot must take active part in the political life of the community and the nation. For unless we meet our obligations as responsible citizens . . . we cannot defeat ignorance and Tyranny.”

The views of the Willard Straight Post were not shared by the heads of the American Legion. The Post lost its Charter in 1931.

When Baldridge was living in Chicago after graduating from the University, he purchased etching materials with the hope that he would have the time to pursue this artistic endeavor. He dutifully packed these materials with each move that he and Caroline made in New York. For some reason, in 1937 (twenty-five years later) he decided to learn how to etch.

After a few attempts he was satisfied enough with a copper plate of a Chinese hawker that he took it to Charles White. Charles White was one of the finest “printers” of etchings of all time. Some of his other customers included Winslow Homer and John Taylor Arms. White was a master at his craft – but he also recognized talent and unbeknownst to Baldridge sent a copy of this etching to James Swann – then the Secretary of the Chicago Society of Etchers.

Swann concurred – Baldridge was a very good etcher. He was so impressed that he invited Cyrus Leroy Baldridge to become a member of the Chicago Society of Etchers – one of the most prestigious organizations in the country.

Here is Baldridge’s Response:

“October 18, 1937

Dear Mr. Swann –

I am much flattered by your letter of the 16th and thank you.

I should be pleased to join the Society. I presume you wish some examples of my stuff submitted? to your next show?

It is only recently that I have done any etchings, after wanting to get at it for many years. And I don’t think I am so good at it yet, either!

Yours truly,

Roy Baldridge

P.S. – I’ve never submitted anything anywhere or shown anything yet.”

(From James Swann Archives – Cedar Rapids Museum of Art)

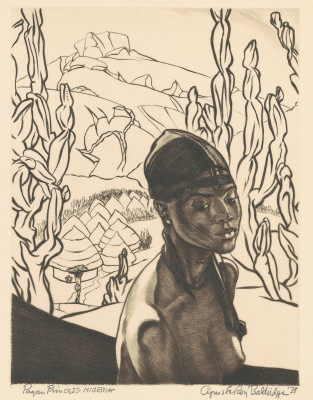

Swann persuaded Baldridge to submit an etching to the Annual CSE Show. The etching Baldridge submitted won the $500 “Members’ Prize” and the “Pagan Princess” became the Presentation Print for the CSE in 1938.

Pagan Princess – CSE Presentation Print 1938

Pagan Princess – CSE Presentation Print 1938

Immediately after having his print selected by the Chicago Society of Etchers, Baldridge was contacted by the Smithsonian Museum with a request for a “one man show” of his etchings. Of course, Baldridge accepted the invitation. There was only one problem. His entire repertoire consisted of four dry-points – two of which were failures. The show was one month away.

In the next 30 days, Baldridge completed 23 dry-points. He did not sleep very much during this period. However, the show went on as scheduled.

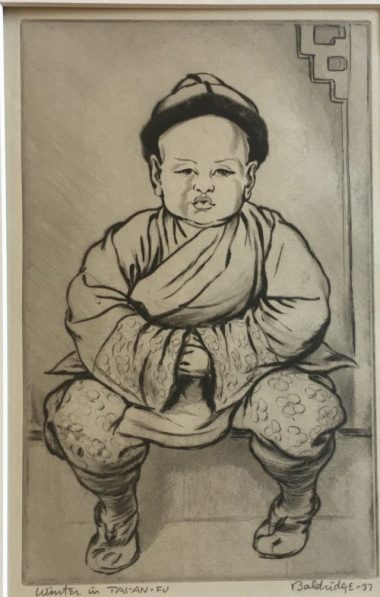

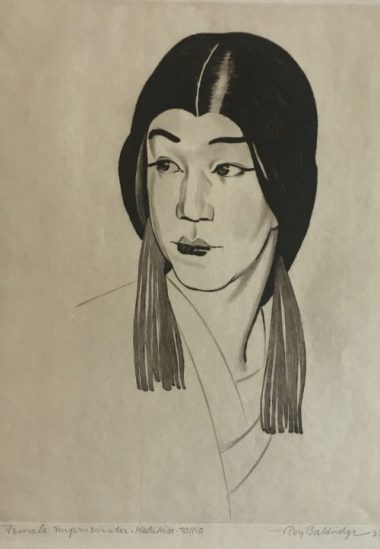

Many of the works created for the Smithsonian Show were based on sketches that he completed on his travels. Consequently, much of his work has a Chinese, Japanese or African theme.

Tai-An-Fu Dry-point (1937)

Female Impersonator (1938)

How could a man complete 23 quality drypoints in 30 days? To make it even more incredible, Baldridge had just started in this medium one year before. Baldridge’s autobiography gives us some insight:

“Opportunity has been kind. Opportunity has in fact been most of the time ahead of my abilities, so that lack of experience has prevented taking full advantage of them – in World War I, for example. But since the start I have always known what I was trying to do; been aware of when the result fell short, and when it almost arrived. Frequent failure has come from attempting tasks beyond my grasp; but I have never lost a conviction that in the field of drawing I could accomplish what my mind saw – given the strength to preserve a critical view of my efforts; given time enough. At inadequacies I have been constantly irritated, but not discouraged.”

The contact between Baldridge and James Swann quickly developed into friendship. Part of the mission of the CSE was to sell the prints of it’s members. Here is Baldridge’s response to receiving a check from the CSE for a show. “Mr. Swann” has become “Jimmie.”

“April 5, 1939

Dear Jimmie –

I am flabbergasted to get that $25.

There must be something crooked about that Chicago Society.

See you soon. Then. Good.

Cyrus”

–Letter from the James Swann Papers – Cedar Rapids Museum of Art

James Swann was drafted into the US Army in 1942. Here is Baldridge’s response when hearing this news.

“Dear Jimmie –

Thanks for the check and for sending the prints.

. . . We can’t pretend that we are very happy about your going off to the wars. I know you are going to “Protect our way of Life” and – all – that. I’d rather it was done some other way.

Of course, now we’re in the war and our side has to win.

But I continue to be resentful that we did not have the statesmanship to recognize and solve the causes.

But now it is too late; and Jimmie’s going to war!

I’m glad you wanted a few prints. Take any others, any time. With your departure from Chicago, I will fold up my etching career. You are mainly the one to blame for it. I’ll await your return. I can imagine that many an etcher will miss you; and the club will probably limp badly for some time.

If by some chance you are stationed in these parts, we’ll expect you to use this as headquarters.

Carry a sketch book!

Good Luck

Roy”

– Letter from the James Swann Papers – Cedar Rapids Museum of Art

James Swann was discharged from the Army in 1943. He served “Stateside” for his entire term of duty.

In 1946, Swann resigned his position as Secretary-Treasurer of the Chicago Society of Etchers due to a controversy with another board member. By 1947 he accepted the same role with the Prairie Print Makers. Cyrus Leroy Baldridge was familiar with this new organization since his drypoint – Soo Chow Canal – had been chosen as their Presentation Print for 1944.

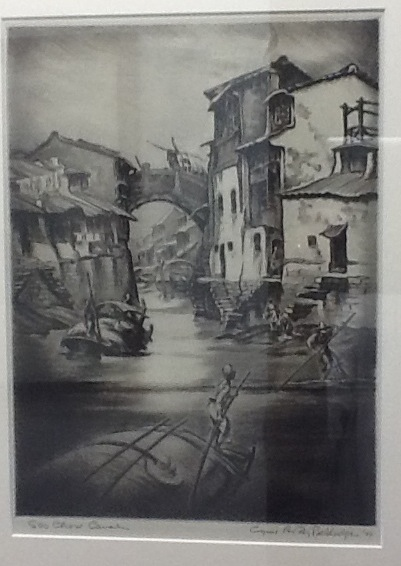

Soo Chow Canal by Cyrus Leroy Baldridge

Soo Chow Canal by Cyrus Leroy Baldridge

The Baldridge’s books sold well. (Roy’s autobiography Time and Chance was on the New York Times Bestseller List for many months.) The income from these sales and Roy’s success as an illustrator provided them with enough money to “retire.” Their plan for the move is outlined in this 1951 letter from Roy to “Jimmie.”

“284 West 11th Street, New York, New York

Jimmie –

Your Oregon Trail sounds exciting.

We have decided to rent this place for Jan – Sept ’52 and try our luck in Santa Fe – see if we’d like it more there. New York gets worse and worse.

Sorry I’ve no prints at all this year – Come around and we’ll tell you our reasons for everything.

Roy”

As it turns out, one of the reasons the Baldridge’s decided to move from New York was that Caroline’s health had been failing and they thought a change of scenery would do her good. They bought a small, comfortable adobe house in Santa Fe and immediately became part of the artist’s group in the city. The plan was that Caroline would write and Roy would be free to do all of the art that he always wanted to do with no worries of the illustrator’s deadlines. Unfortunately, Caroline’s condition did not improve in the new environment. She was no longer able to write. A later diagnosis determined that she had had a series of small strokes that impaired her writing ability.

In Santa Fe Roy devoted most of his artistic energy to oil painting. He hiked and drew most of the mountains and forests of Northern New Mexico.

But Jimmie Swann – Roy’s biggest fan – had more plans. In 1953 Swann had participated in a show at the California State Library. He was so enamored with this venue that he proposed that they have another show in 1954 featuring (of course) – Cyrus Leroy Baldridge.

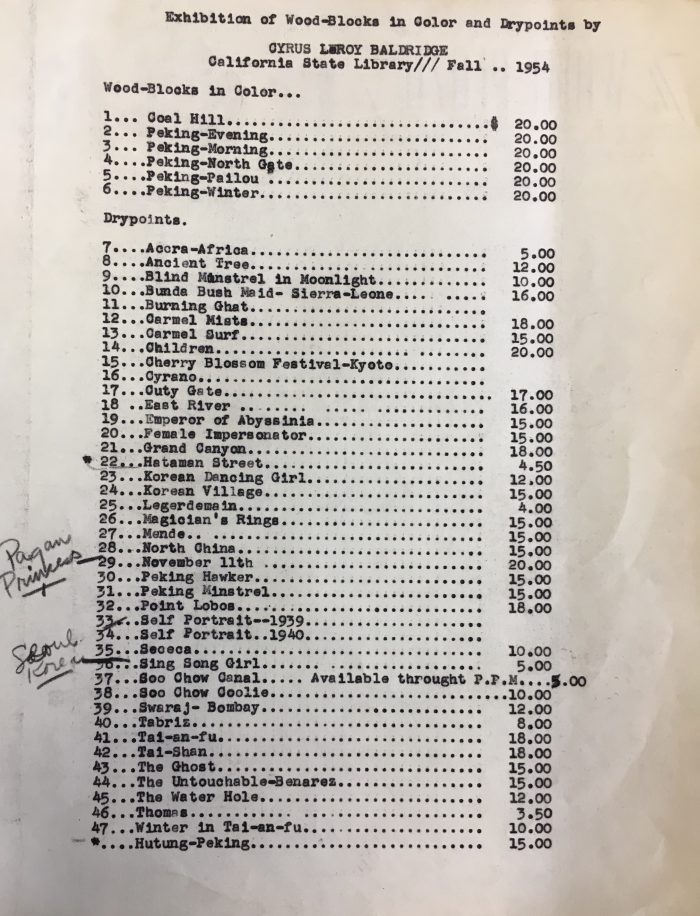

In preparation for the show, Swann put together a list of all of the woodcuts and drypoints by Cyrus Leroy Baldridge. It serves as a “catalogue raisonne” of Baldridge’s work.

Baldridge Print List from James Swann Papers – Cedar Rapids Museum of Art

You will notice that Baldridge also did a few color woodcuts. He learned this skill on his trips to the Orient. As you can see by this woodcut, he created some impressive work.

Peking Winter by Cyrus Leroy Baldridge (Color Woodcut)

Swann had big plans for the Baldridge Exhibit at the California State Library. In an August 11, 1954 letter to Baldridge he explained that he hoped to “show fifty prints as I don’t want any other artists to have anything on view during this exhibit. In case there are some of your prints that you don’t wish to show, would it be possible to send along a few sketches of the Southwest . . . and I will mat them in clean and uniform mats.”

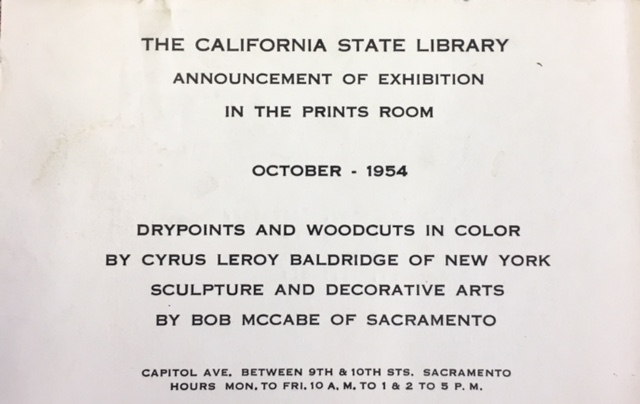

Apparently the sketches were not necessary since only drypoints and woodcuts were shown as indicated on this announcement:

The show was a success and the Library, Swann and Baldridge were all very pleased. As Baldridge said in a letter following the show:

“Dear Jimmie

You are good to spend the time on an exhibition for me. Though I don’t know why you do it. As an etcher, I am pretty much a has been. However, thanks.”

One motivation for Swann was monetary. In the 1950’s James Swann had slowed down on making his own etchings. He had developed a good business selling the prints of other artists. His connections with many artists through his position as Secretary-Treasurer of both the Chicago Society of Etchers and the Prairie Print Makers gave him the best sources of prints. In fact, by the mid 1950’s he had converted part of his house into an active gallery and had over 10,000 prints in his inventory.

In a letter from Swann to Baldridge on September 10, 1954, he listed recent sales of Baldridge prints. Swann had sold 8 prints for a total value of $117.00. He lists his commission of 1/3 at $39.00 and includes a check for $78.00 to Baldridge.

To give some idea of these amounts in today’s dollars, the second half of the above mentioned thank you note from Baldridge to Swann gives some “room rates” in Santa Fe in 1954. (Swann was an active traveler to New Mexico in the 1950’s.)

“Motels here are $5 to $6. Single room at La Posada (now remodeled) 5 or 6. The de Vargas is OK. $2.50 for single, without bath. Bath, $4. If you are in need of a bath, we’ll give you one for a quarter. And there are several other hotels in the de Vargas class.”

Swann and Baldridge continued their correspondence and friendship for many years. An undated letter from the Swann papers gives us a good idea of their easy-going rapport and the status of many of the oil paintings that Baldridge had created in New Mexico.

“Jimmie

It was friendly of you to remember my birthday.

Evidently you have not heard that I have given up birthdays. Too many of them.

No special news here except that the town is growing. Like in all the world, population is getting us down.

I still paint pictures. And have luck giving them away. The University of Wyoming requested some for their new Art Museum. They walked off with 50. (Professional appraisal = $25,000. But even if I go back to birthdays, my income tax deduction will never catch up with that!)

Good luck,

Cyrus”

Caroline never recovered from her mini-strokes and passed away in 1963. Roy continued hiking, painting and the camaraderie of his fellow artists in Santa Fe. By the mid 1970’s his health and mind started to decline. On June 6, 1977 he ended his own life with a bullet from a handgun he had been issued in World War I.

This is the best short study of Baldridge I have come across.

He was a remarkable artist and he was one of the finest men I ever knew. He deserves recognition.

Good work!

Thank you. I had collected some of his prints several years ago. This Spring I was working in the James Swann Archives at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art and came across the correspondence between Baldridge and Swann. No doubt he was a fine artist, but what comes through in his letters is his intelligence, his caring for others, his modesty and his capacity to be a true friend. You are fortunate to have known him.

Hello Me. Rosenthal,

I greatly enjoyed your article on Cyrus Leroy Baldridge. I have a framed oriental painting signed “Baldridge” and I would love to know if it an original or a print. U purchased it at an estate auction several years ago and know nothing about it. And guidance would be greatly appreciated!

Glad you enjoyed the article. In all probability you have an original woodblock print. It is my understanding that most of his work with an oriental theme were color prints. Send me a picture of it at jimrosenthal5757@aol.com. I might be able to identify it for you.

Jim —

I have read your piece on Cyrus Baldridge with great interest. Cyrus was a close friend of my family while he lived in Santa Fe and I have recently done a great deal of research on his work. I also have a very large collection which includes art work, papers and letters.

Your piece had some things that were new to me, and I would enjoy learning where you got your information. I did not know nearly as much about Swann as you revealed, for instance, though I have some items that refer to him. I also did not know the way that Cyrus met Caroline or how he ran into her later.

Well, there is plenty your could teach me and probably some I could teach you. If you are interested contact me at JayMulberry@gmail.com.

Best regards,

Jay

Jay

I would love to learn more about Cyrus Leroy Baldridge (I guess his friends called him Roy). You are welcome to email me directly at jimrosenthal5757@aol.com.

Most of the information about his life I obtained from his autobiography – “Time and Chance.” Apparently, the book sold well and the proceeds helped the Baldridge’s in their retirement in Santa Fe. I bought mine from a used book seller on ebay.

James Swann was a friend and business associate of my father, Charles Rosenthal. When Swann moved to Chicago in 1936, he apprenticed with Morris Henry Hobbs in the Tree Studio Building at 4 East Ohio. Hobbs and Swann worked in Studio 21. My grandfather and father worked in Studio 20 – across the hall. Swann is mentioned in my father’s autobiography. When my father passed away I inherited some his James Swann prints. Thus, my interest in going to Cedar Rapids to go through the James Swann Archives at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art.

The letters quoted in the above article come from those Archives. As mentioned in the article, Baldridge’s printmaking career pretty much revolved around his connection to Swann. But for me the most interesting part of their correspondence is to see how their friendship developed over the years. It went from “Mr. Swann – Secretary of the Chicago Society of Etchers” to “Jimmie” who is welcome in my home at any time. I did not copy all of the letters between the two in the files. However, I would be glad to share any of the copies that I have.

Hopefully, you will be able to write more about Baldridge. Both he and Swann deserve all of the recognition we can provide.