One night in May of 1927, a young artist by the name of Levon West was at dinner with friends when he heard the news about an aviator named Charles Lindbergh who had taken off in his “Spirit of St. Louis” airplane to be the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic. West remembered that he had seen the plane a few days before at Roosevelt Field on Long Island and had sketched it. He left his friends and went to his studio to create an etching of the plane in flight. After working all night, the etching was completed. He rushed over to the New York Times to find that Lindbergh had landed in France, and the paper was about to be printed announcing the achievement. The etching was the perfect complement to the lead article. But how much did West want for the etching? His response was, “I don’t care how much I get for it, but put my name on it good and big at the bottom.” The Times used the etching on the front page and it was picked up by papers across the country. The etching career of Levon West was off and running. Kennedy and Company, the leading print dealer in the US, signed him the next day.

Levon West etching “Newfoundland” (Lindbergh’s Flight)

Levon West etching “Newfoundland” (Lindbergh’s Flight)

Levon West was born in Centerville, South Dakota on February 3, 1900. His father was a Congregational Minister of Armenian descent and his last name was Assadoorian. Both of Levon’s parents saw his interest and talent in art and encouraged his early development as an artist. When it came to a career, however, his father had some doubts about art as a way to make a living. West graduated from his high school as the Valedictorian. But the WWI draft called and he spent a year in the US Navy. At that time he changed his name to “West” in honor of the most noted member of his mother’s family, Benjamin West, the famous American/British portrait painter of the late 18th and early 19th century. All of his active-duty time was spent Stateside and he was released from the Navy in early 1919.

His next step was the University of Minnesota. His father insisted that he take all business courses – which he did – but he made friends in the Art Department and audited several courses in Art. He contributed drawings to the school newspaper and was eventually made art director of the publication. After graduation, he took a small studio in Minneapolis, where he did illustrations for various advertising agencies and publications.

In 1924, he travelled to New York on the way “to seek a business degree” at Harvard Business School. Once in New York, he caught the art bug again, and he decided that he wanted to pursue a career in art. He sought out the noted printmaker and teacher, Joseph Pennell. West enrolled in the Art Students’ League where Pennell was an instructor. Pennell immediately saw the potential in West and encouraged him to pursue a career in art. That was all West needed. He did his first etching in October of 1925. Pennell added a few drypoint lines for instructional purposes. The result was a good etching entitled “Lunch Hour.” West did 6 more etchings on his own and then followed the path of many artists – he moved to Europe to finish his art education.

Instead of choosing Paris like most of his contemporaries, he moved to Spain. He spent most of 1926 there – travelling, sketching and learning. The vast majority of his etchings from 1926 and early 1927 are of Spanish scenes and people. West lived the life of the proverbial struggling artist until he returned to America in the spring of 1927. Then came May and Lindbergh.

West’s fame was such that by 1930, Otto Torrington had already created a catalogue raisonne of his works entitled “A Catalogue of the Etchings of Levon West.” This was, and is, unheard of. A catalogue raisonne is usually created after a long and successful art career – many times posthumously. West had his published just 3 years after achieving renown.

To provide an idea of the extent of West’s popularity, I did an analysis of the etchings listed in the Torrington work. West created 69 plates from 1925 to May 1927, when the Lindbergh etching was done. The total number of etchings pulled from these plates was 807, or about 12 per plate. He produced 55 plates from May 1927 to the publishing date of the book in 1930. The total number of etchings pulled from these plates was 5,005, or more than 90 per plate. There is no guarantee that all of these etchings were sold. But since virtually every plate created after 1927 had 100 numbered impressions and from 6 to 22 “trial proofs,” it appears there was sufficient demand to justify the supply. West printed all of his own etchings. In effect he turned his etching press into a money-making machine.

Levon West understood what would sell – art that people liked and understood. His realistic style was, and is, very appealing to the eye. His use of space, contrast and a minimal number of lines made his work stand out. Many of his pieces shared the theme of the human struggle against the elements – whether it was desert, mountains or blizzard – as an added interest for the viewer. He also did many etchings of dogs, famous people and outdoor sports like fishing and hunting.

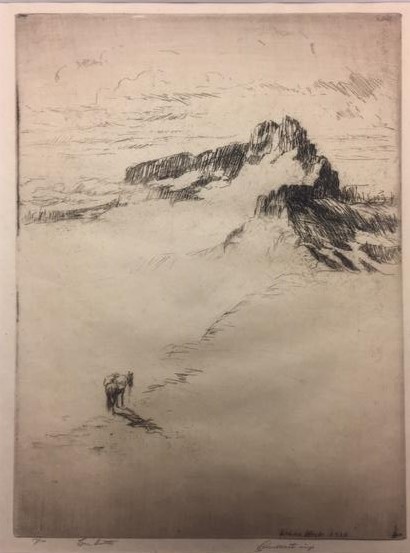

Lone Butte – 1928 – (Torrington #115)

Lone Butte – 1928 – (Torrington #115)

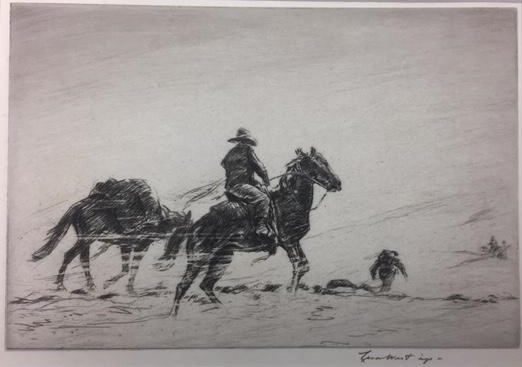

Riders in the Snow – 1935

Riders in the Snow – 1935

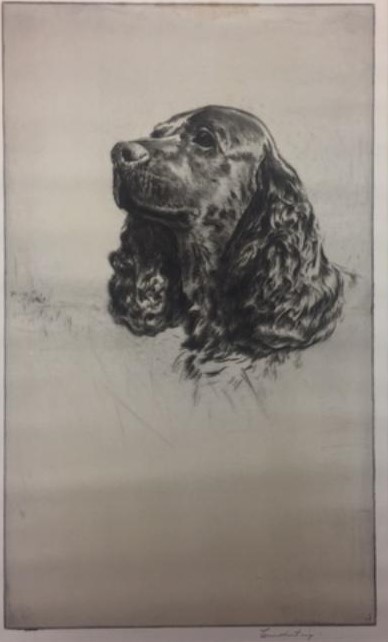

Cocker Spaniel (Champion Torohill Trader)

Cocker Spaniel (Champion Torohill Trader)

Some claim that West lacked creativity, since he focused on themes that people found appealing. His work was criticized for not being very original or meaningful. Yet it was popular and appreciated by a large segment of the buying public. That was West’s measuring stick, and it told him he was taking the right path with his work.

An Englishman, Malcolm Salaman, was considered the world’s leading expert on etchings and engravings in the 1920’s and 1930’s. He edited the influential and highly regarded Fine Prints of the Year: An Annual Review of Contemporary Etching and Engraving from 1923 to 1935. (Campbell Dodgson edited the last three editions from1936 to 1938.) Inclusion in this work was considered to be a high honor, and a sign that an etcher or engraver had reached the upper echelon of the print world.

Well known artists like Frank Benson, John Taylor Arms and Martin Lewis were consistently included. Benson and Arms were in the Fine Prints of the Year for 13 straight years while Lewis was in it for 12. Arthur Heintzelman was the leader among American etchers with 16 straight appearances. Levon West was in 8 yearly editions – virtually his entire active etching career. His first appearance was in the 1928 edition and the last one was in 1936.

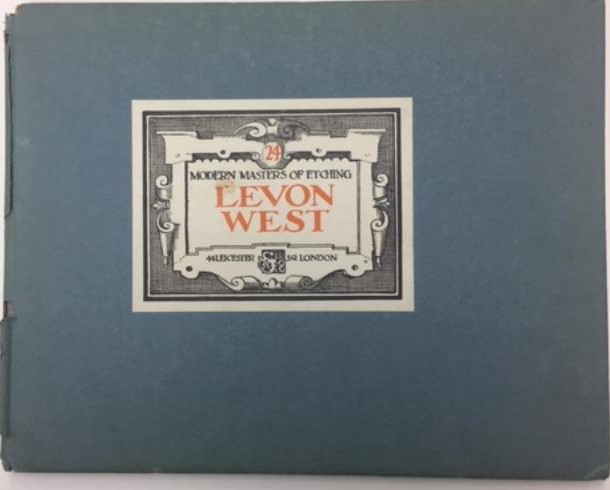

Malcolm Salaman was very prolific. He not only edited the Fine Prints of the Year, he also wrote and edited a book series entitled Modern Masters of Etching. The artist subjects included Anders Zorn, James McBey, Frank Benson, Sir Francis Seymour Hayden, James McNeill Whistler, Francisco de Goya, Rembrandt, and Louis Rosenberg. The 24th Volume, published in 1930, was done on Levon West.

Modern Masters of Etching – Levon West – 1930

Modern Masters of Etching – Levon West – 1930

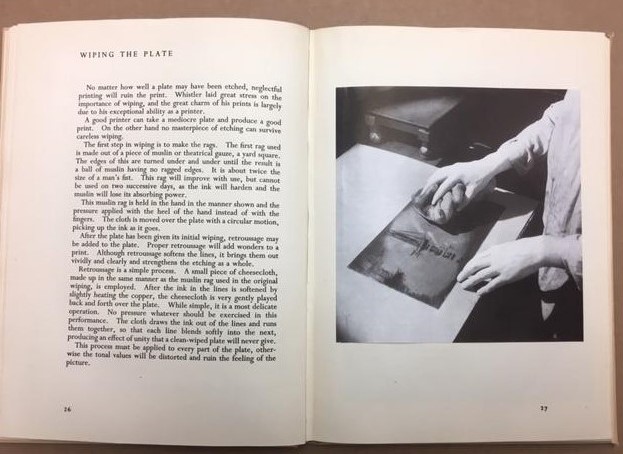

Salaman also had a hand in another popular art book series called the “How to Do It” series. This featured step-by-step instructions on how to do everything from wood engraving (written by Clare Leighton) to photography (written by Ansel Adams) to art lithography (written by Stow Wengenroth). The first book in the series, which eventually included 37 volumes, was Making an Etching by Levon West, published in 1932. The book is clear, well-written and concise. It takes a very difficult subject and makes it seem easy (it’s not). West also analyzes the etching technique of 20 well-known etchers.

“Wiping the Plate“

From “Making an Etching” by Levon West

All of these things confirm the fact that Levon West established himself as one of the leading artists (etchers) of the late 1920’s and early 1930’s. But timing is everything, and there is such a thing as being in the right place at the wrong time. The stock market crash of 1929 plunged the US into the Great Depression of the 1930’s. Surprisingly, the art and etching market did not follow the stock market – at least in the beginning. The 1929 crash reduced stock values by 90%, but prices in the fine print market only dropped about 50% in 1929-1930. Unfortunately, several things were happening that virtually wiped out the sale of etchings by the middle of the decade.

First, it took a couple of years for the effects of the crash and the downturn in the economy to be felt by print collectors. Most of these people were professionals or business owners who saw some relative bargains in lower print prices. By 1932 the effects of the Great Depression were widespread and the number of buyers dropped dramatically.

Secondly, the print dealers encouraged continuing high levels of print production. West and others likely kept producing new plates and pulling one hundred or more etchings per plate. Soon supply outstripped demand, and prices plummeted.

Thirdly, art tastes were changing. Modernism was on the rise, and representational art like that of Levon West lost popularity. Other print-making techniques like stone lithography, wood engraving and woodcuts were on the rise. In fact, by 1934 Fine Prints of the Year included prints made with these methods for the first time. In addition, half of the prints selected were to be “modern” and the other half would be more traditional. Ralph Pearson was asked to select the modern group while Ernest Roth chose the others.

Fourthly, the art world has always had an on-and-off relationship with color in prints. By 1933, the love of black and white prints was cooling. Sales suffered accordingly.

The result was that by 1935, the handwriting was on the wall. It was no longer possible to make a reasonable living creating, printing and selling etchings. Etchers went in all directions to make enough money to make ends meet. Many went into the illustration of books, magazines and advertisements. Some went into teaching. Some were temporarily supported by the government art programs of the WPA. Others went back to their old professions, including drafting and architecture. Levon West took a totally different path – color photography.

Color photography was relatively new in the mid 1930’s. West had little experience in the art form of color photography, but as we have seen, he was a quick learner. To preserve his legacy as an etcher and to avoid confusion, he changed his name. As a photographer, he became Ivan Dmitri. And Dmitri had just as successful a career in color photography as Levon West enjoyed in etching. Once Levon West, the etcher, became Ivan Dmitri, the photographer, the transformation was complete. Levon West never did another etching.

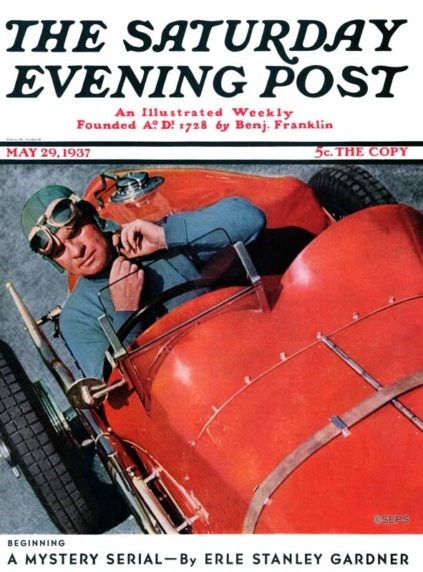

Incredibly, by May of 1937 a color photo by Ivan Dmitri was on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. The SEP was one of the most prominent magazines, if not the most prominent, in the country. The Norman Rockwell covers on this magazine were the vehicle that made him a household name and sustained his popularity. Just a year after he had given up etching, Ivan Dmitri was well on his way in his second career.

Ivan Dmitri would go on to provide color photographs for 10 more Saturday Evening Post covers. But his first (seen above) may be his most memorable. It was taken at the Indianapolis 500 race, another American institution.

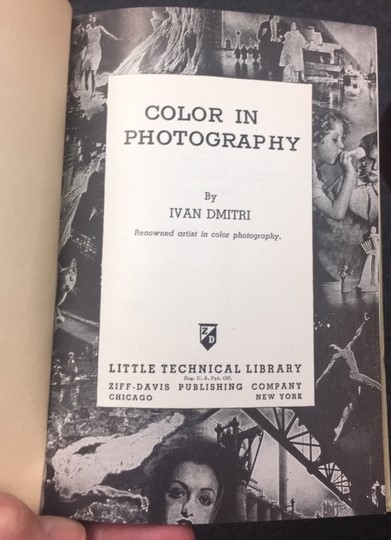

Dmitri’s color photography work output grew exponentially. His photographs were everywhere, from travel posters to mail order catalogs. Just as he had done in etching, he wanted to teach others how to create quality color photographs. In 1939, his book Color in Photography was published as part of the Little Technical Library. This little (4 3/4″ X 5 1/4″) book became the go-to manual for amateur color photographers. It is clearly written, with lots of practical how to information and photos. This book and the three others written by Dmitri helped to secure his place in the American mind as one of the country’s top color photographers.

Ivan Dmitri had a gift for being able to “teach” through the written word. His “Color in Photography” was one of the most popular instructional manuals of this era.

Ivan Dmitri had a gift for being able to “teach” through the written word. His “Color in Photography” was one of the most popular instructional manuals of this era.

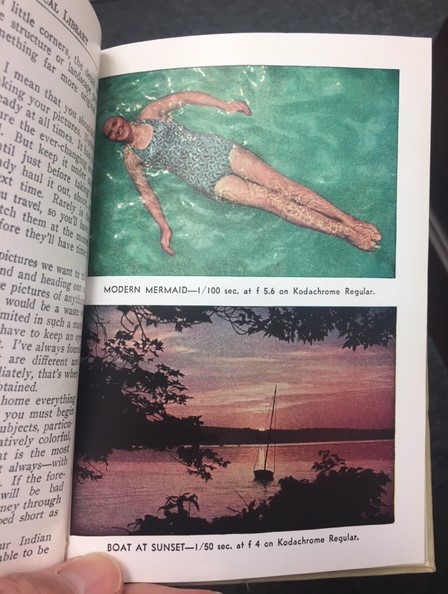

This page is typical of the book. Good photographs (I love the 1939 – “Modern Mermaid”) and clear instructions – shutter speed, f-stop and film used.

This page is typical of the book. Good photographs (I love the 1939 – “Modern Mermaid”) and clear instructions – shutter speed, f-stop and film used.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor changed everything immediately. The United States went from a country that was trying to stay out of the war to a nation totally committed to winning WWII. This transformation affected all aspects of American life, including art and color photography.

Ivan Dmitri was not one to sit idly by on the sidelines. He talked the Saturday Evening Post into making him one of their war correspondents. The resulting journalistic and photographic journey and experience is a remarkable story, and a tribute to his 100% commitment to everything he did.

War reporting often focuses on battles and the front line action of troops in combat. But the engine that drives all activity in war is logistics – getting the weapons, men, food and materiel to the right place at the right time. As we have seen, Dmitri loved aviation. So Dmitri’s choice for his work was the United States Army Air Corps Air Transport Command (ATC).

By 1943, he had already flown an incredible 36,000 miles and visited virtually every sector of the ATC’s work – from the deserts of North Africa and the jungles of Asia to the frozen tundra of Greenland. He was constantly sending back photos and reporting for publication in the Saturday Evening Post. The resulting book from his work in the field was appropriately named : Flight to Everywhere, published in 1944.

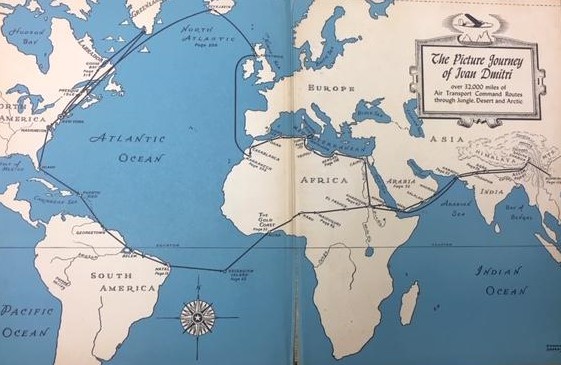

The inside cover of the “Flight to Everywhere” with a map of the 36,000 mile route that Ivan Dmitri took to report on the US Air Transport Command in World War II.

The inside cover of the “Flight to Everywhere” with a map of the 36,000 mile route that Ivan Dmitri took to report on the US Air Transport Command in World War II.

Those 36,000 miles were not flown on a 747 with first class accommodations. They were flown in crowded air transport planes designed for delivering supplies, not people. They were crowded, slow and uncomfortable. When they had seats, they were those known as “bucket seats,” which according to Dmitri were the “malicious variation of the cup-shaped resting place for man’s posterior adorning the farmer’s plow.” After a 12-hour hop in an air transport plane’s bucket seat, he claimed that the passenger should receive “at least a service bar of some sort, with a minimum of one Oak Cluster or, better yet, a Purple Heart.”

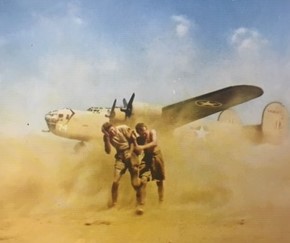

Flying as a passenger with the Air Transport Command was seldom a good experience. The planes were crowded and uncomfortable.

Flying as a passenger with the Air Transport Command was seldom a good experience. The planes were crowded and uncomfortable.

Dmitri (left) with Sgt. Willie McGee in the jungles of India.

Dmitri (left) with Sgt. Willie McGee in the jungles of India.

Many ATC airplanes traveled the “Southern Route” to Europe. This meant two or three stops in South America, then flying to Ascension Island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

Ascension Island – This 34-square-mile island served as a vital refueling point for aircraft crossing the Atlantic. Best described as a “pile of rock.” It has little vegetation and no economy. US troops built a 6,700 foot landing strip on the island in 91 days in 1942.

(Note: My father-in-law, Ken Roman, served as a navigator in the US Army Air Corps Ferry Command. This was the part of the ATC that ferried airplanes from the manufacturing plants in the United States to North Africa and Europe for the Allied Air Forces. He made a number of trips across the Atlantic that included a stop at Ascension Island. There was no GPS in those days – navigation consisted of a combination of interpreting the position of the stars, determining wind direction and speed by observing the waves on the Ocean, dead reckoning and luck. The trip from South America to Ascension was over 1,000 miles, but woe be it to the navigator who missed the island. The usual response was to turn the plane around and give the navigator something more than a gentle ribbing. Unfortunately, since the island represented the outer range of many aircraft’s fuel supply, the outcome was often more severe. Lieutenant Roman never missed the island.)

Dmitri’s photographs and articles represented a tribute to the soldiers and civilians who served in the Air Transport Command from:

The deserts of North Africa

The deserts of North Africa

to

The jungles of India and China

The jungles of India and China

to

The Frozen Actic

The Frozen Actic

He told their story – of facing the dangers of war as well as their hard work and sacrifice. In the foreward to Flight to Everywhere he says:

“I hope this book will serve as a diary for the men themselves. It is a small offering, awkward and unmasterful in its execution, but it has wonderful subject matter – heroes and the deeds of heroes. I wish I were more capable of doing it justice.”

The men and women of the Air Transport Command appreciated his efforts. The biggest compliment to any artist is the purchase of their work. My copy of Flight to Everywhere bears the inscription: “Property of Fred Ehman – Air Transport Command – Group 376 – Squadron 512.” I am sure that Mr. Ehman was not the only member of the Air Transport Command who proudly owned one of Dmitri’s books.

After World War II, Dmitri continued his career as a commercial photographer. He enjoyed considerable success, and was a frequent contributor to publications such as Life Magazine and the Saturday Evening Post. His major commercial clients included General Electric and Trans World Airways, and he did a considerable amount of business with the tourism and catalog industries.

By the late 1950’s, Dmitri decided that he still had to fulfill one of his long-time desires: he needed to do what he could to ensure the place of photography as a fine art. At the time photography was considered by many to be a “craft.” The argument went something along these lines: Anybody could activate the shutter of a camera. The camera itself performed whatever artistry was represented in a picture, providing instant capture of whatever striking scene presented itself. The film supplied the color combinations, and what the film failed to do, the printing shop was able to offer. All sorts of mechanical leeway were available to camera operators.

Today, few would argue that photography is not an important part of the fine arts. Almost every museum has a curator of photography. Most people understand and appreciate the artistry of a fine photograph – just as they appreciate the artistry of a fine painting. Dmitri played an important role in this transformation of public opinion.

In 1958, he wrote an essay for the Saturday Review extolling the virtues of photography as a fine art. The thesis of the essay was that “picturemakers are able to establish the same sort of emotional experience that one enjoys reading a good book or watching a great play.” Dmitri wrote, “The use of composition and design, arrangement of form, spontaneity and a host of other qualities make a great photo. Photography is not mechanistic. In its truest form it is creative and artistic.”

The editors of the Saturday Review were sold, not only by Dmitri’s essay, but by the response of art museums and the general public. They agreed to sponsor his efforts to create a museum show entitled “Photography in the Fine Arts.” The show was to be held at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Director of the Museum, James Rorimer, was named Chairman of the Selection Committee.

Dmitri was appointed director of the project and his first task was assembling as wide an array of photographs as possible. He contacted magazines, photo agencies, industrial photo libraries, publishers of photography books, heads of the photography departments at many universities, photo organizations and the larger camera clubs. By mid-January of 1959, this call had resulted in 438 photographs for final consideration. The next step was the formation of the selection committee.

Dmitri recruited a group with varied backgrounds and viewpoints. It included such luminaries as the editor of Art News, the president of Hallmark Cards, the senior art director of McCann-Erickson, the director of the Addison Gallery of American Art, the art editor of Life, the art critic of The New York Times and the curators or directors of the Museum of the City of New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art. Stanley Marcus of Neiman-Marcus was also a member. There were a total of 14 judges in all.

The judges selected a total of 85 photographs from 55 photographers. Works by Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Ernst Haas, Richard Avedon and many other well-known photographers were included. The exhibit opened at the Metropolitan on May 8, 1959. It was immediately hailed and condemned. Ironically, much of the uproar came from photographers who were not included – proving in an odd sort of way that photographers were indeed “artists.”

Criticism of the exhibit focused on three main points – One, the judges were not qualified to make selections on the artistic qualities of photos; two, many of the best photographers were not part of any of the submitting groups and were excluded; and three, there were questions about how works by amateur photographers could be shown alongside those of established photographers. Some thought there were too many portraits and nature scenes. Others felt that “one lucky shot” could make for inclusion in the exhibit.

But just like most of the things Dmitri did, it was an immediate public success. The exhibit was eventually shown at 26 art museums across the country, and total visitors exceeded two million. The popularity of the Photography in Fine Arts (PFA) exhibit was so high that plans were immediately put in place for a PFA II. PFA II was twice the size of the original, with 176 photos from all over the world. By 1963 a total of four PFA exhibits had been organized and shown with similar outstanding results.

In 1965, Eastman Kodak decided to build a pavilion at the New York World’s Fair. Photos from the four PFA shows were featured. They were divided into groupings based on the selections of the different museum directors and curators who were on the selection committee.

The last exhibit in the series, PFA V, opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in March of 1967. Levon West/Ivan Dmitri died on April 25, 1968, and he did not have a successor. In all, the Photography in the Fine Arts exhibits had been shown in 150 art museums and university art galleries and were viewed by more than 8 million people. By any measure, the exhibits played a large part in achieving Dmitri’s goal of changing the public’s perception of photography. It is indeed a fine art.

Ivan Dmitri was an inveterate note-taker and organizer. His voluminous files from his career were originally donated to the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian. When staff members started to inventory the material, they realized they had all of the materials for not one, but two, people – Levon West and Ivan Dmitri. The Smithsonian kept the Levon West records and gave the Ivan Dmitri files to the International Center of Photography.

Levon West – famous etcher. Ivan Dmitri – famous photographer. The same remarkable person.

(Special thanks to John Rohrbach, Senior Curator of Photographs, Amon Carter Museum of American Art and Kristen Gaylord, Assistant Curator of Photographs, Amon Carter Museum of American Art for their helpful assistance in the research on the “Photography in the Fine Arts” part of this article. It is much appreciated.)

Note:In 1988 the ICP organized a major travelling exhibit from this collection. The accompanying book is entitled: Master Photographs: From ‘Photography in the Fine Arts’ Exhibitions, 1959-1967. The curator of the ICP, Miles Barth, selected the photos for the exhibit and contributed one of the essays in the book.

February 21, 2022

Dear Jim- just tripped back on your wonderful and comprehensive article on Levon. I have a pencil signed etching by both Levon and Charles Lindbergh of his 1927 portrait. Love to talk, but first you can email. I am a psychiatrist in Annapolis Maryland. Thanks! Richard

The Lindbergh portrait is pretty special. It is #71 in the Torrington Catalogue. (75 numbered impressions. 18 trial proofs.) The fact that it is signed by Lindbergh and West adds to the value. I am glad you are enjoying it.