Things were going well in the art world of Gerald Geerlings in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s. After serving in the US Army during World War I, he had graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Architecture but decided that he would like to follow his love of creating art. Despite the coming of the Great Crash in 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression of the early 1930’s, his etchings were selling well and he was making a decent living from his art.

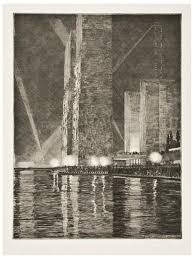

Electrical Building at Night – Chicago Century of Progress World’s Fair (1933-34)

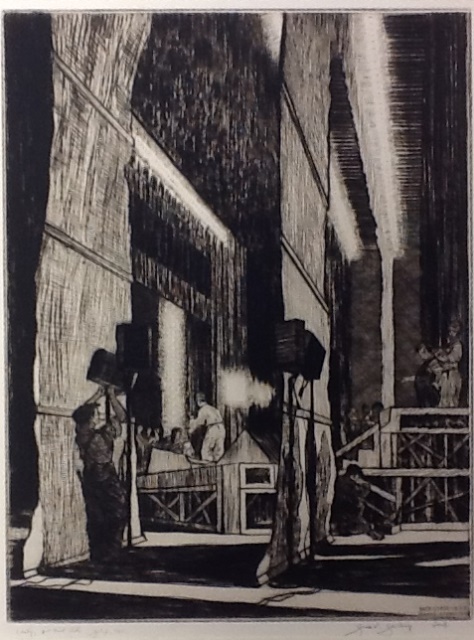

Back-Stage – 8 PM (Grand Opera – 1932)

His “Electrical Building at Night” (1933) etching won the competition for the best etching of the Century of Progress Chicago World’s Fair. He received a $500 prize and the etching was also chosen as the 1933 Presentation Print for the Chicago Society of Etchers. This income and the sale of other etchings made a good living for Geerlings. In fact, it was enough for him to spend 6 months a year in London to work on his art.

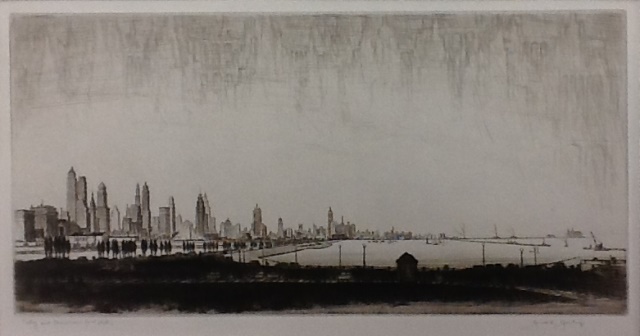

Today and Tomorrow! (Chicago 1933)

(It is difficult to see in this reproduction, but the clouds in the sky include faint outlines of many more skyscrapers presumably that will be added to the Chicago skyline in the future.)

Flash forward just a couple of years and the market for etchings had dwindled to next to nothing. Like many etchers of his era, Geerlings was represented by Kennedy and Company of New York. In a later interview he recalled how from time to time he would stop in at the Kennedy Gallery and found the “absolute stillness unnerving” and would ask if there was “any justification for new plates.” By this time his income from prints had become “almost negligible.” He resorted to illustrating architectural articles to support his trips to London to focus on his etching.

However, this was not a satisfactory solution to his problems in that: “I found it impossible to have a dual personality: on the one hand, trying to etch on a copper plate a ‘social document’ or a distilled cityscape portrayal, entirely divorced from any thought of financial reimbursement; and on the other hand, being a combination of craftsman, architect, and wordsmith, with financial involvement.”

By the late 30’s Geerlings had totally abandoned his print making and made his living as an architect, illustrator and author. Then along came World War II. He enlisted in the US Army Air Corps and played a key role in improving the accuracy of Allied bombing of Germany.

Before the War, he frequently flew on commercial airlines and enjoyed drawing his views from the air. Using his artistic skills and this experience, he drew maps of targets for the bomber pilots to follow. His efforts were so successful that he was honored with the Legion of Merit. He continued to do work for the Strategic Air Command until 1952.

Geerlings continued his combination of writing, illustrating and architecture until the 1970’s. Although the sales of works on paper grew substantially during the 50’s, 60’s and early 70’s, it was centered on non-representational, colorful “modern” work and not on the type of art Geerlings enjoyed. He stayed on the “sidelines” of the creative art world.

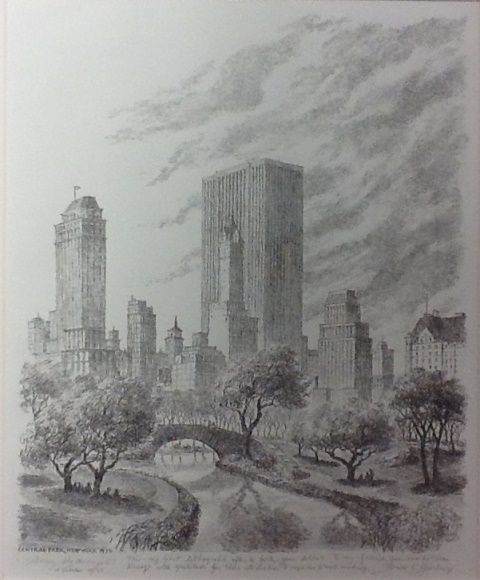

Enter June and Norman Kraeft. These two individuals did as much as anyone to bring about the renewed interest in black and white, representational prints created from 1900 to 1950. Their gallery and shows focused on work from this genre and era. They wrote articles and books on the subject. (Their book “Great American Prints 1900-1950” is one of my favorites.) They traveled the country giving lectures at art museums and other venues. They also encouraged artists who had “dropped out” of printmaking back to their studios. One of these artists was Gerald Geerlings. I own a lithograph entitled “Sing Hallelujah!” that tells the story. The inscription on the bottom reads:

“This – my first lithograph after a forty-year detour – to my friends June and Norman Kraeft, with gratitude for their stimulus to resume print-making. Gerald K. Geerlings – 16 October 1975.”

Sing Hallelujah! (Central Park, New York) 1975

Geerlings second career in creating art took off in the 1970’s and 1980’s. He created many lithographs of New York and Paris. He was also commissioned to do sketches of Paris and produced over 150 pen and ink drawings of the city.

Another individual who was instrumental in encouraging Geerlings was Joseph Czestochowski (Director of the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art). Czestochowski put together a Catalogue Raisonne of Gerald Geerlings work. In 1985 he also organized a show of his etchings and lithographs that was presented at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, at the Chicago Historical Society and at the Museum of the City of New York. The show featured 23 pieces and was critically acclaimed. An article on the show in the Chicago Tribune appeared with the headline: “Architect Geerlings Turned Etchings of Pre-War Skylines into High Art.”

Gerald K. Geerlings died in Connecticut in 1998 at the age of 101.

Leave a Reply