Bertha Jaques was one of the original founders of the Chicago Society of Etchers. More importantly, she was the Secretary and inspirational leader of the group from 1910 to 1937 – a total of 27 years. One of her major roles was to help organize the Annual Exhibtion of Etchings for the CSE . Her booklet, originally written in 1912, entitled “Concerning Etchings” was sold at the yearly Exhibition for over 40 years. Bertha Jaques did over 450 etchings herself, kept meticulous notes on her work and had a deep understanding of this art form. The original booklet has been out of print for over 50 years (There is a recent reprint.), but it still represents one of the most succinct and clearest explanations of the art of etching. The following is an excerpt from Bertha Jacques’ “Concerning Etchings.” (Images from our collection and notes have been added by the author.)

“It has been said that in studying prints one should look for an adequate thought adequately expressed; freshness of conception; artistic vitality; excellence of design; draughtmanship; and clearness of the print impression.

Joseph Pennell, with the clear incisive touch of an etcher, is quoted as saying that ‘a great etching by a great etcher, is a great work of art, displayed on a small piece of paper, expressed with the fewest, vital indispensible lines, of the most personal character; a true impression of something seen – something felt by the etcher, something he hopes some one may understand and care for as he, the artist, does.’

Etchings are not drawings made with pen and ink, nor are they reproductions by photography. They are printed from a copper plate upon which lines have been etched, or deepened by acid, hence the name etching.

The plate is of polished copper, or zinc, about a sixteenth of an inch thick. In order to subject it safely to the action of the acid, every particle of the plate must be covered with some protecting substance. This is found in a preparation of wax, asphaltum and pitch, technically called a ‘ground,’ which is melted and rolled thin on the hot plate. When cold this thin covering forms a smooth, hard surface through which lines are drawn with a sharp steel point, called a ‘needle.’

Drawing

Some artists work directly upon their plates with the needle from nature as they would sketch with pencil and paper. In this case, the drawing when printed, will be in the reverse. Others make careful drawings with ink or pencil and transfer them to the copper plate in reverse so the picture when printed will be correct. The transferred lines are visible on the wax ground and may be traced with the needle.

This method insures greater accuracy of drawing and placing, as all corrections may be made before transfer; but the careful procedure is not likely to convey the spontaneity and freshness of inspiration that is apparent when a well-directed needle records the impressions of the moment upon the copper itself.

As the lines are not only drawn through the wax, they must be made permanent in the copper. Taking advantage of the fondness of certain acids for corroding metals, nitric or nitrous acid, is used to complete the work of the artist.

Biting

Some etchers use drops of strong acid on the plate, moving it about with a feather to bite groups of lines deeper than others and complete the biting without stopping out any portion.

Others prepare a bath of acid and water, consulting the thermometer as to whether it shall be a strong solution in cold weather, or weaker in warm weather. Only porcelain or glass dishes may be safely used for this purpose. Supported on waxed strings for holders, the plate is just submerged into the acid, which at once attacks the copper wherever the needle has laid it bare. Then the interesting process manifests itself by little opalescent bubbles that form and crowd each other off the lines.

If the drawing has been made with a finely pointed needle, the acid is used to vary the depth of the line. For very fine lines, the plate may be left in the acid two minutes, more or less, when it is lifted out by the strings, washed and carefully dried and the finest lines covered with a small brush and ‘stopping-out-varnish.” The plate is returned to the acid and lines of the next strength exposed for ten minutes, or longer, when the previous process of washing, drying and stopping out, is repeated. In this way the work is carried forward until there may be lines in the sky bitten two minutes, and strong deep lines in the foreground bitten for one or more hours.

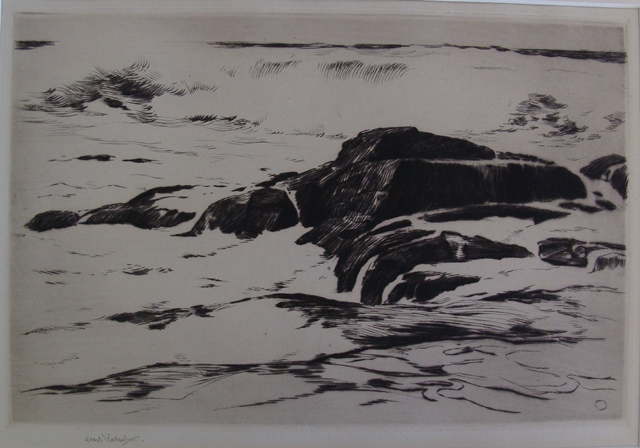

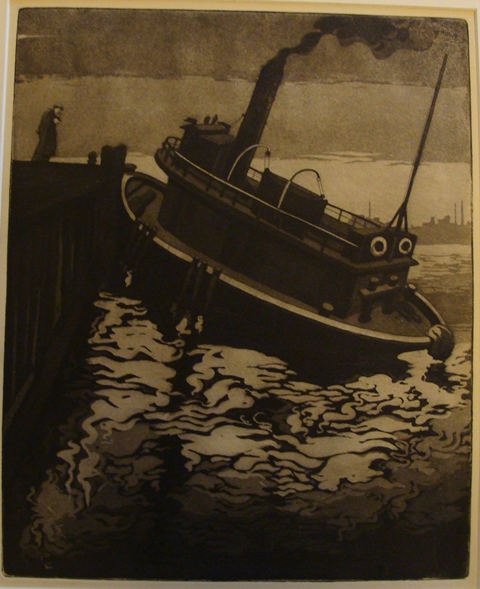

This etching done by Sears Gallagher (1869-1955) illustrates the biting of the plate with one exposure to the acid bath. All lines are the same intensity. He achieves the sense of depth in the print by varying the number of lines in the surf.

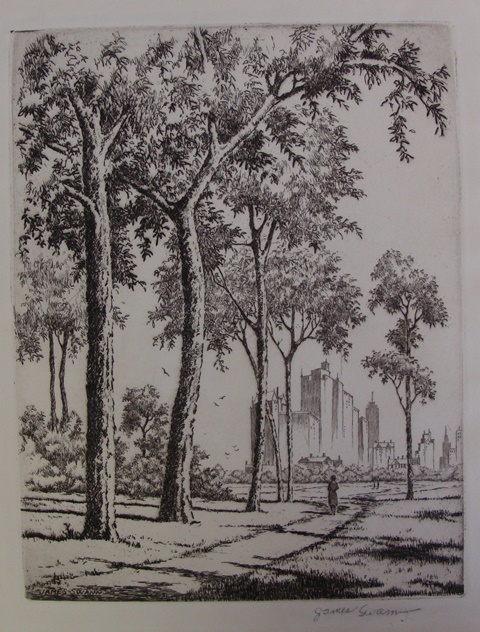

This print by James Swann (1905-1985) illustrates how depth can be conveyed in an etching by varying the amount of time the plate is exposed to the acid during the biting process. The buildings in the distance were created with a short exposure to the acid bath. Then they were covered with “stopping out varnish.” The trees in the foreground were created by a longer “biting” time to give deeper and thus sharper lines.

Some etchers vary their lines by drawing with fine and coarse needles, giving but one biting to the plate. Others work on the plate while it is in the acid, putting in the heaviest lines first and ending with the lightest.

There is no way of determining, except approximately, just what the etching is doing, or how deep the lines are, until the wax ground is removed (which is quickly done with heat and kerosene or turpentine) and a print made.

There are three distinct opportunities for failure in making an etching: in the drawing, in the biting and the printing. An artist may be an excellent draughtsman and draw lines on the copper faultlessly, but the etching will not be a success unless he possesses the knowledge of how to bite the lines into the copper.

He may possess the skill to draw and bite, but his plate will be as useful as a photographer’s glass negative unless he can print it. Many etchers do not attempt the printing, but leave it to professional printers, who follow the artist’s direction as to how he wants the etching to look.

The most satisfactory results are obtained when the artist does his own work, from the first drawing to the final print. But the expense of the necessary equipment is such as to prohibit etching as a mere pastime, and the practice necessary to acquire skill in printing plates is such as to put it out of the hands of most etchers for anything but the simplest proofs of their work.

The chief joy of an etching is its spontaneity. In the hands of a skillful worker, it may be rushed to completion and the etcher may look upon the moist print of his copper plate before the white heat of his enthusiasm cools. This joy is unknown to the artist who must send his plate to a professional printer for a proof. Even a day is too long to wait, and a day must turn into weeks. So the etcher who can take his plate out of the acid, wash and dry it for the last time, warm and remove the wax ground, and turn at once to his press to prove his hopes, is the only one to taste the full fruition of pleasure in his work.

Printing

A thoughtful etcher will have prepared his paper before he began his plate, by dipping it in water, or sponging it, and putting it in little piles between blotters upon which are heavy weights. If he grinds his own ink, which is made of fine black powder and oil, this is also ready.

With a smooth roller, or a dabber, the thick ink, that stands up in shiny heap, is forced into the lines. The whole surface of the plate is solidly black. With a pad of open-meshed cloth, the ink lying on the surface of the plate is carefully wiped off, leaving the sunken lines full. At this point there are so many methods of manipulation to produce various effects which would only be interesting or comprehensible to a printer. Both the bare hand and cloths are used to free the plate from superfluous ink and yet leave what is necessary to produce the effect desired.

The plate is then warmed and laid on the iron plank of the press; over it is laid a sheet of paper moistened with water until it is limp and soft, but not wet. Over this are placed several fine white filt blankets, woven for this purpose. Then the plank passes between two heavy steel cylinders exactly as a clothes wringer, coming out and stopping on the other side. The pressure is as heavy as it can be and allow the plank to pass between the rollers.

The soft blankets force the moist paper into the lines, which takes up all the ink it finds there. When the blankets are lifted, and the paper peeled off the copper plate, permanently embossed upon it will be the ridges of ink that filled the etched lines, together with any tone left on the surface.

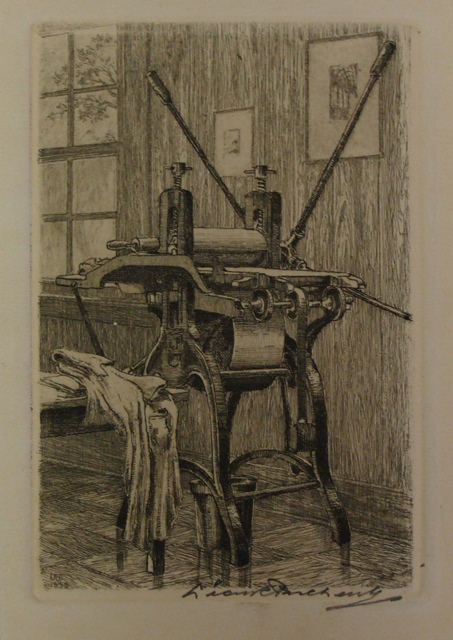

This Leon Pescheret etching shows a typical etching press used in the 1920’s and 1930’s. The design has not changed much since then. The inked etched plate, the moistened paper and the cloth “blankets” are placed on the bed. As the “star handles” are turned, the bed advances under the roller, applying pressure that forces the ink from the etched lines onto the paper. Since the plate has been forced into the paper, it leaves an indentation which is clearly visible on the reverse side of the etching.

This is the most crucial moment in the whole work of etching. Up to this time, there is no certainty of what has been accomplished. The lines may be clearly seen upon the plate, but it is not enough to merely make a line. There must be fine lines, heavy lines, deep and shallow lines, black lines, gray lines and rich, ragged lines. The success of the biting lies in the quality of the lines. Hence, it is a staid old heart that does not quicken when the first proof of an etched plate is lifted.

Alterations

If the proof is satisfactory, the plate is ready for further printing. If some lines are too heavy, they are first scraped with a sharp-edged scraper, burnished with a smooth burnisher, and rubbed down with fine charcoal and a buffer, reducing them to the desired depth. If lines are too light, the plate may be again covered with a wax ground and the lines bitten deeper. Lines may be added, or erased, but never with ease; it is a slow and tedious process to make alterations on a plate.

Some years ago the purchaser of fine prints thought it necessary to be familiar with the different stages through which engraved and etched plates, principally translations of other pictures, passed.

A few impressions were printed while the artist was yet at work on his plate and these were called “artist’s proofs” simply because they were proof, or evidence to the artist of what he was doing.

The name of the painter, whose work was being engraved, together with that of the engraver, were added in small letters to the plate and a few more impressions taken which were designated as “open letter proofs.”

Lastly, the outline letters were solidly filled in and an edition printed called the “letter prints.”

Neither this knowledge, nor that concerning “remarque” proofs is necessary to the understanding or appreciation of modern painter-etchings, and these facts are only noted here to clear away the confusion regarding them.

The “remarque” which does not correspond to our word “remark” but means “a proof bearing a special mark,” is recorded as having originated in the thoughtless scratching of the artist on the margin of his plate while at work, perhaps to try him needle. These scratches sometimes took shape in a slight sketch which appeared in the trial proofs but were burnished out before the plate was finally printed.

Collectors knew that prints bearing these marks were trial proofs and therefore early ones; hence, eagerly sought for them. Profiting by the hint, publishers encouraged artists to draw a sketch on the margin of the plate and after a stated number of impressions were taken, the sketch was burnished out.

Etchers like Sir Seymour Haden, Whistler, Pennell, Cameron, Zorn and others, have never recognized or used the “remarque” and it has no place in the best modern etching. In fact, there is seldom any margin to spare for extraneous sketches as etchers now usually fill their plates to the outside edge with their subjects, leaving no wide surface for the printer to labor over.

While proving their plates, artists may work directly upon them with the needle or graver, putting in lines or burnishing them out. The critical connoisseur will define these stages as different “states,” first, second, third, or any number representing a recognizable change. The painter-etcher’s only idea is to reach a satisfactory state where the plate may remain unchanged through its final printing, and this most desirable achievement is sometimes accomplished with the first proof.

This work by Levon West (1900-1968) entitled “English Bay” is an excellent example of several points raised in the text. First, it is an etching and drypoint. The major lines were etched into the plate and then highlights and modifications to the etched plate were done with the drypoint needle. Secondly, according to Otto M. Torrington in his “Catalogue of the Etchings of Levon West” it is the third “state” of the work. Slight modifications were made to satisfy the artist and improve the etching. Thirdly, it is an example of how the artist can improve the appearance of the etching by the way he wipes the ink from the plate. The shading in the corners of the etching has been created by leaving ink on the plate in these areas during the ink wiping process.

The paper takes all the ink out of the lines, and it must be re-inked for each printing. As each copy receives individual treatment, it is almost impossible to make all prints exactly alike. A commercial printer can do it but an artist seldom cares to. The variations of paper, ink and treatment are the modulations of his musical theme, and raise what would be mechanical drudgery in printing, to an art.

Every manipulation of the plate, such as putting ink on, wiping it off, and passing it through the press, wears off an infintesimal layer of copper. In time the plate becomes so worn that the values of the line are lost; then the etching is no longer what it was intended to be and the plate should be destroyed.

If lines are deeply bitten, it will take longer to wear them down; hence, an etching with heavy lines will yield more copies than a delicate one. A deeply bitten plate should yield one hundred or more prints. Shallow lines make far less and drypoints give fewest of all.”

Drypoint

“Although classed with them, a drypoint is not an etching because its lines are not etched with acid. They are cut directly into the copper by a sharp needle with the use of wax ground or acid. The needle cuts throught the copper, throwing up a bur, as a plow turns up a furrow in the soil. This bur on the edge of a solid line, holds the ink and spreads it, making a richer, more velvety line than one that is etched twice as deep. But it is easy to see how a shallow line with a shaving of copper will wear away very quickly in the printing.

Hence, drypoints are limited in edition. Sometimes three or four, or even on perfect print may be made and the plate destroyed. Etched plates are made artificially rare and more expensive by limiting editions to stated numbers and destroying the plate. This is done upon the principle that rarity constitutes value whereas the artistic perfection of the plate alone should determine its value.

The work here considered is painter-etching, or original work by the artist on copper; not translations, or etchings which reproduce the work of another artist.

It may not be amiss to mention, very briefly, other methods of making fine prints since they are more or less associated. All incised work, whether on metal or wood, comes under the general head of engraving. This word is also used to describe the impression taken from an engraving plate, the making of which is entirely different from etching.

Engraving

Upon a steel, or copper plate, V-shaped lines are cleanly cut with a tool called the burin or graver. They are stiff and formal; an etched line is not. Engraving works more for tone; etching does not. There can be no freedom to a line that is pushed forward with a tool resting against the palm of the hand. If a magnified section could be seen, the engraved line would be like the letter V; an etched line would resemble the letter U; and a drypoint line would be like a plow furrow. All these are inked and printed in much the same way with very different results.

This is a view of an engraved, un-inked plate with a microscope. What you see is the center of an “O” in the text on the plate. Note the sharp, well-defined lines.

This is a view of an etched, un-inked plate with a microscope. Shown is the silouette of a man from the rear. The lines are much “looser” and will provide a “softer” image on the printed page. They are also more of a “U” shape with a rounded bottom versus the “V” shape of the engraved lines.

Associated with engravings, etchings and drypoints, are mezzotints, aquatints and woodcuts. The latter are chiefly seen in recent years as color prints, made from blocks of wood upon which the lines to be printed stand up like type, instead of being indented like the etched, engraved and drypoint lines. Mezzotints and aquatints are somewhat similar in effects but are quite differently made. Both are capable of the most exquisite gradations of tone.

Mezzotint

In preparing a copper plate for mezzotint, the entire surface is made rough by a tool with hundreds of fine teeth called a rocker, because of the motion used. A print of the plate in this state would be solid black. The lights of the picture are scraped and burnished down, the highest being made by the smooth copper. This is working from dark to light instead of the reverse as in etching or engraving.

Aquatint

For an aquatint, a copper plate is covered with a fine resinous dust that adheres in fine particles with heat. The back is varnished and the plate bitten in weak acid. High lights are painted out before biting, and further gradations of tone are accomplished, just as in etching, by stopping out. The result is a grained surface, instead of lines, which holds the ink in its different depths. Mezzotint and aquatinted plates wear rapidly in printing as does the drypoint, because no small projections of copper can possibly wear as long as a deeply indented, or etched line.

This aquatint by William Sharp (1900-1961) is an excellent example of what can be done with this technique.

Color

The color of an etching is due to the color of the ink it is printed with. There may be color in the picture where there are no lines at all and this is a thin film of ink left on the surface of the copper plate. An effect of twilight may be given by a tone of ink alone, or the plate may be entirely cleaned, leaving the paper as white as that outside the plate line.

This method of clean printing puts the whole burden of the story on the lines. If they are not expressive and full of quality, the picture might as well have been drawn with pen and ink. But a printer with a painter’s touch knows how to make hard line sympathetic and draws them all together with a bond of tone.

Paper

Both paper and ink are large factors in the success of an etching. Any plate that can stand thest of white paper and black ink is sure to be excellent, for it is a severe combination. Ink that is slightly warmed by brown and printed on paper of a creamy tone is generally more pleasing. Rich brown ink on a deeply toned soft Japan paper is still more mellow, but not brilliant. Japanese vellum has a creamy surface flecked with light that gives proofs with an old ivory tint. But all Japanese papers grow woolly with handling and are difficult to clean. Handmade papers are desirable for their texture and lasting qualities. Most attractive of all to the etcher are the precious sheets of old paper made in the fifteen, sixteen or seventeen hundreds, some of which are still discoverable in old shops in Italy, Germany, France and Holland.

Many a rare proof is printed on a ragged, worm-eaten sheet of paper on the other side of which may be some accountant’s notes of three hundred years ago.

Margins

The size of these pages has been the cause of very narrow margins and this, as well as the expense of fine paper, leads etchers to waste none of it in wide margins outside the plates. This is of no concern since fine etchings should be protected with a mat up to half or quarter of an inch of the plate-line, having the signature of the etcher exposed.

Signatures

As etchings are frequently printed on soft, or unsized papers upon which writing ink would spread, and it is sometimes necessary to dampen prints, they are only signed in pencil. This also far outlasts the writing ink. This is the written approval to the purchaser that the etcher has looked upon his work, finds it satisfactory and signs his name to it. For this reason, signed etchings are considered more valuable than those with no signature. But this fact only applies to comparatively modern work as the custom of signing has not been in general use for more than thirty years. Many of the old masters had a monogram, or device, which they etched in the plate and this the work was frequently identified. Up to the present day, some artists etch their names in an inconspicuous corner, as well as the title of the picture, thereby making the record permanent.”

Good article (in Dutch) on Bertha Jacques. Very interesting.