By Jim Rosenthal

The “Renaissance Man” is defined as someone who is knowledgeable, educated and proficient in a wide array of fields. The best example is Leonardo da Vinci. The best example in Chicago for the first half of the 20th Century was Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

Seymour was a man of many talents. He was an accomplished publisher of fine books, the creator of many book plates, and an excellent etcher. He was widely travelled in Europe and the Southwestern US. He was an active member of many organizations including “the Cliff Dwellers,” the Caxton Club, the Chicago Society of Etchers, the Lake Zurich Golf Club and many more. His list of friends included Clarence Darrow (attorney), Frank Lloyd Wright (architect), Daniel Burnham (architect), Bertha Jaques (etcher), Robert Frost (poet), Ezra Pound (poet), Elbert Hubbard (author), Lorado Taft (sculptor) and Jane Addams (Founder of Hull House). In fact there were few in the art, business or social world in Chicago in the early 1900’s who did not know and appreciate the talents and friendship of Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

He was born on March 18,1876 in Milan, Illinois but spent most of his childhood in Indiana. As Seymour describes in his autobiography – Some Went this Way – he was an undistinguished student in high school. In fact, his mathematics teacher made a special point of telling him that he was “no good in grammar or in Latin, and you certainly are dumb in mathematics.” But he was right when he added: “I think someday you will be a good artist.”

Seymour went on to study at the Cincinnati Art Academy under Frank Duvenek, Lewis Meakin and Vincent Nowattny. He moved to Chicago in the Autumn of 1898. His first job was at an engraving house drawing and lettering newspapers and advertisements. He worked in a “bull pen” with twenty other workers. Since the country was still recovering from a depression, his pay was zero. After two months, he received his first weekly pay – $2.00.

Fortunately, this engraving house was an “incubator” for young artists. One of his co-workers was Joseph Leyendecker. Joseph and his brother Frank proved themselves to be outstanding artists. Their work on advertisements and book illustrations was immediately noticed and was soon in high demand. Other contemporaries of Seymour in Chicago during this time were Jules Guerin, Harrison Fisher, Maxfield Parrish and Childe Hassam.

Soon Seymour was moving on to bigger things. While at the Art Academy in Cincinnati, he developed a fondness for fine books. In his spare time in Chicago, he hand lettered a version of Shakespeare’s “Three Merry Old Tales.” He used his savings to print a full first edition with the anticipation of easy sales. Obviously, books do not sell themselves and sales were not good. Good fortune struck when a friend of Seymour’s gave a copy of his book to Frank W. Gunsaulus. Gunsaulus was President of a college, friend of many mighty men in business, and a great book lover. The retail book trade in Chicago gave him the nickname of “The Saint.”

“The Saint” loved “Three Merry Old Tales” and offered to send his card with Seymour’s promotional material on the book. Book sales rolled in. The full edition was soon sold out. Ralph Fletcher Seymour was in the book publishing business – a field that he stayed in for over 60 years.

By the time Seymour had published his third book it was obvious to him and to his employer that he needed to find another place to run his burgeoning publishing business. After to talking to friends, he concluded that the Fine Arts Building on Michigan Avenue was the place he needed to be. The building was filled with artists of all kinds – from musicians to architects to painters to sculptures – you name it. On a visit to the building he struck up a conversation with Charles Francis Browne, a noted landscape artist and publisher of a Chicago art magazine. As it turned out, Browne was leaving for his summer home and he offered the free use of his space. Obviously, the price was right and Seymour moved in.

The offices were actually sublet from the Lorado Taft – one of the leading sculptures in the country during the early 1900’s. It did not take long for Seymour to convince Taft that he would be a good tenant, neighbor, and friend. Seymour’s publishing house had a permanent home and it was a perfect fit for his personality. He was in the center of the art, business and cultural world of Chicago and he thrived.

This picture is taken from the grounds of the Art Institute of Chicago.

One block to the right is Chicago’s Orchestra Hall. (home of the Cliff Dweller’s Club during Seymour’s era. Seymour was an active member.)

The 10th floor of the Fine Arts Building was an active place. Of course, Lorado Taft was his neighbor. Just down the hall were the offices of Frank Lloyd Wright. Besides being a world renowned architect, Wright was also a collector of Japanese prints. Seymour and Wright became friends and Seymour went on to publish a book on Wright’s prints.

Seymour had many interests and was involved in many civic, cultural and fraternal organizations. His autobiography is filled with stories of the Cliff Dwellers, the Caxton Club, Ravinia, his nude models (somewhat risque, but never over the line), the publishing industry and his many friends of all walks of life. He was entertaining, talented, interesting and interested. Most importantly, he was a protagonist in and teller of great stories. But all of this is beyond the scope of this blog post. He was also an accomplished etcher and printmaker and that is the story we would like to tell here.

According to Seymour’s autobiography, he began his etching career by being included as an original member of the Chicago Society of Etchers. This group was started in 1910 at an evening meeting at the home of Bertha Jaques. In attendance were Ms. Jaques, Ralph Pearson, Otto Schneider and Earl Reed. Their goal was to create an organization for the promotion of etching and etchers. They achieved their objective. The Chicago Society of Etchers became one of the most important artistic societies of the early 20th Century and was successful for over 40 years. The definitive book on the CSE is Bertha E. Jaques and the Chicago Society of Etchers by Joby Patterson. In this book and in the Seymour autobiography, he is listed as one of the “charter” members. (A letter from Seymour to Jaques that I found in the James Swann Archives at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art raises some questions about this timing, but we will address that later.)

In addition to running his publishing business, Ralph Fletcher Seymour was a teacher at the Art Institute of Chicago. He taught classes in lettering and graphic design. At that time the Art Institute sponsored one teacher per year to study in France. He was chosen for this honor in 1912. His account of his many European adventures take up about 40 pages in his 300 page autobiography. Obviously, the experience had a big impact on his life.

(Author’s note: I was fortunate to have a similar experience in 1968-1969 when I attended the Netherlands School of International Business at Nijenrode outside of Amsterdam. It is amazing how one year can change your thinking and broaden your horizons.)

One of Seymour’s goals for his Parisian adventure was to learn how to be an etcher. Luckily two of his Chicago friends – Otto Schneider and William Auerbach-Levy – were in Paris and willingly agreed to be his teachers. Even though he was an accomplished artist, he literally had to (excuse the pun) start from scratch. His year was well spent learning everything from how to ground a plate . . . to how to design and needle the work . . . to how to use acid to etch the results. He also learned how to choose the right printer for his etchings. When he returned to Chicago he had many of his etchings printed by Henry Rosenthal (my Grandfather) and his son Charles Rosenthal (my father).

Seymour soon became a very accomplished and enthusiastic etcher. By 1915 he was ready to apply to the Society on the basis of his etchings. Here is his letter to Bertha Jaques from the James Swann Archives at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art:

“The Chicago Society of Etchers – to Mrs. Bertha E. Jaques, Secretary

“Dear Madam – It has taken me over a year to find time to write this letter of application for membership in the Chicago Society of Etchers, although I have more interest in belonging to so important an organization as it has proved to be than in almost any other affiliation.

With this letter I send, in your care, 5 proofs of plates which I have etched, and printed, also. I wish to be made a member, if the low quality of the work, which is, nevertheless, the best that I can offer, will permit you to accept me.

After your decision will you kindly return the examples to me, and inform me of the Society’s action as to my application, and greatly oblige.

Very truly yours, R. F. Seymour (February 4, 1915)”

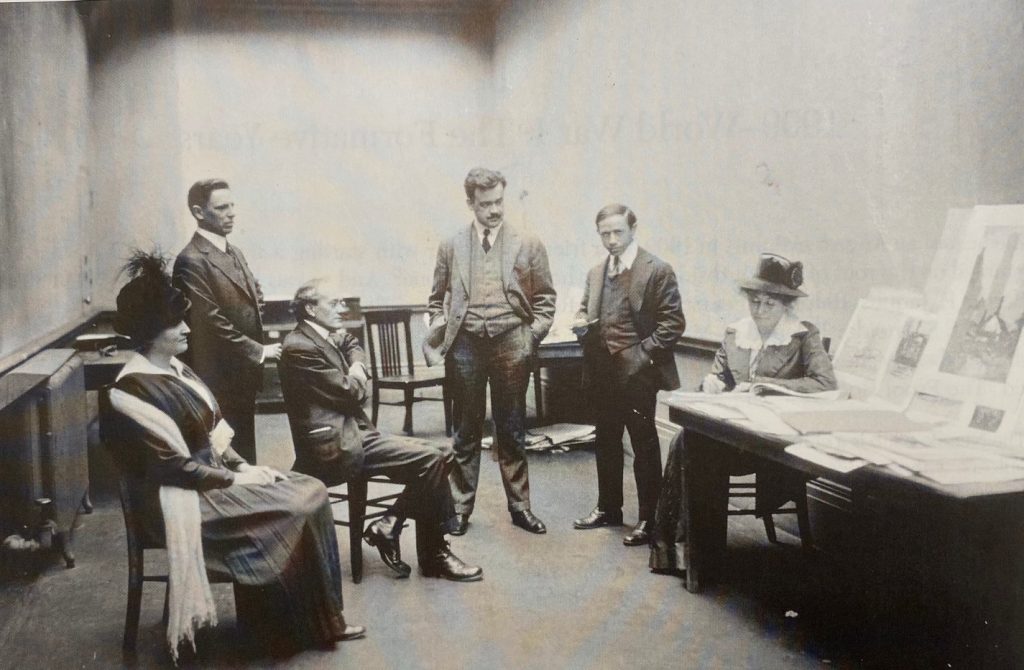

His application was accepted. As mentioned above, Seymour loved being involved in organizations, clubs, groups and any other activity where he could interact with people. He was a talented etcher and he knew everybody. It did not take long for Bertha Jaques to include him on the Jury that decided who would be able to participate in the annual show of the Chicago Society of Etchers. In the early days these shows were held at the Art Institute of Chicago. They attracted top etchers from all over the world. Being included was a big plus for an artist’s etching career. Prints were also sold at the show and this was a major income generator for the participants.

By 1917 Seymour was made one of the judges for the show. He served in this capacity at least until 1927.

The Chicago Society of Etchers had two types of members – artist and Associate. The Associate Members paid $5 a year. This money covered the expenses of the organization. Each year Associate Members received a Presentation Print created by one of the artist members. The Presentation Prints were selected by the CSE Jury of Selection. For more information on this program and a full listing of all Presentation Print winners see:

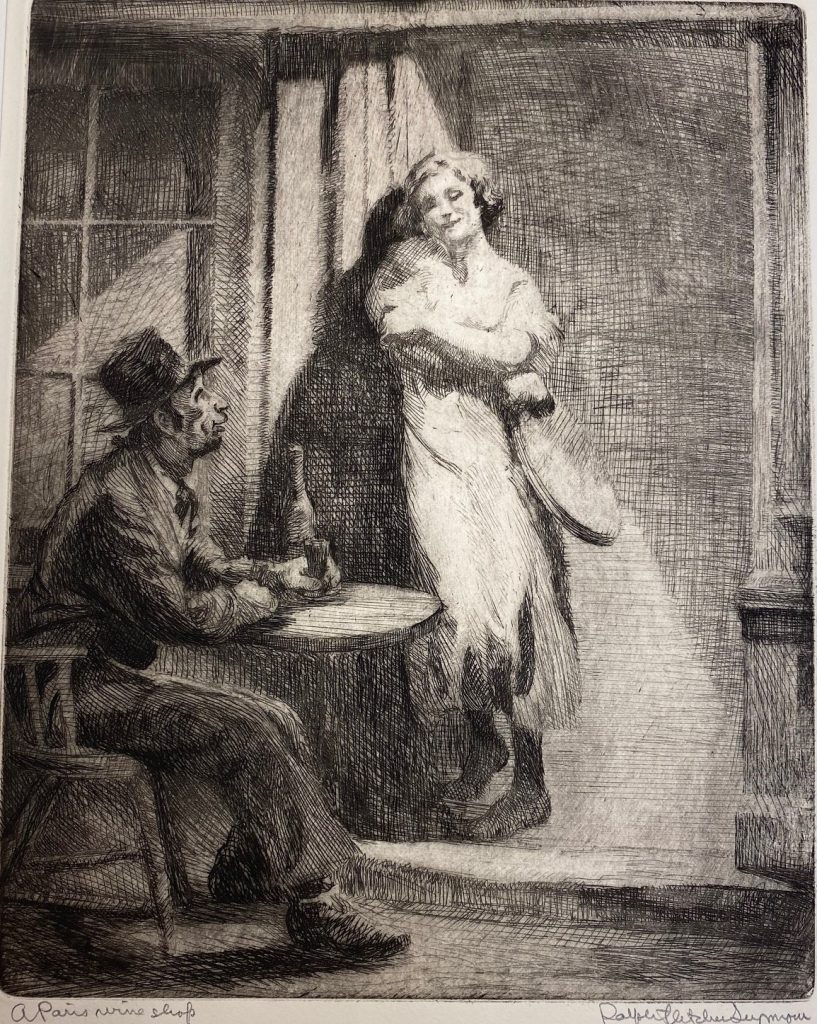

www.inpraiseofprints.com/chicago-society-of-etchers-presentation-prints-1912-1956/An etching by Seymour was selected as the 1935 Presentation Print. It is entitled “A Paris Wine Shop” and was printed by Morris Henry Hobbs.

Chicago Society of Etchers

Seymour’s social satire was in high gear when he created this etching. His use of light emphasizes the contrast between the two figures. The young and attractive waitress bathed in sunlight visiting with the older and somewhat homely patron in the shadows. Surely the patron was certain in his own mind that he became wittier and more intelligent with each glass of wine. It is doubtful the waitress was impressed – except maybe with the gratuity.

(When Seymour returned from Paris, he started teaching etching at the Art Institute. One of his pupils was Morris Henry Hobbs.)

Seymour was a prolific etcher. In fact, he created etchings much like many artists do sketches. Charles Rosenthal in his autobiography describes delivering printed etchings to Seymour in the Fine Arts Building. As he was accepting the prints, he was talking with a visitor and etching a 5″ by 7″ grounded plate. To the astonishment of Charles, he finished all three in a span of about 15 minutes. Consequently, just about any scene that he encountered in his daily life could be the subject of an etching.

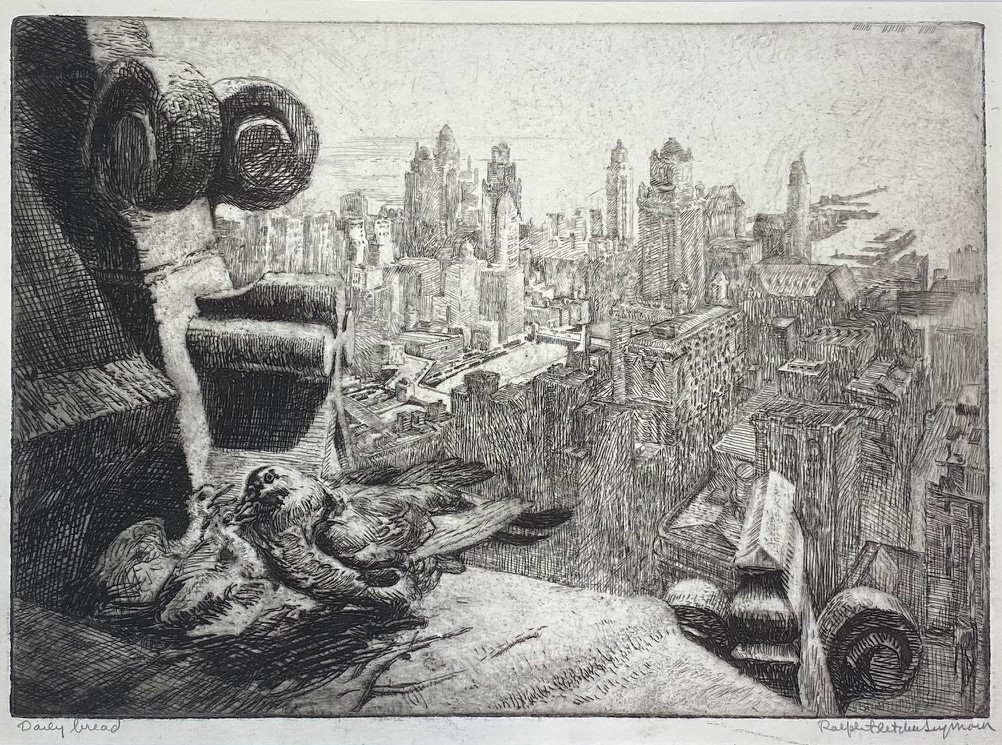

For example, one of his friends enjoyed feeding the pigeons on the window sill of his office. After a visit, Seymour decided to memorialize the act and the view. The result was one of his most famous etchings – “Daily Bread.”

By Ralph Fletcher Seymour

(This print is also in the National Gallery of Art donated by Reba and Dave Williams. Dave Williams’ book – Small Victories: One couple’s surprising adventures building an unrivaled collection of American Prints – is a great book on the joys of print collecting and well worth the read.)

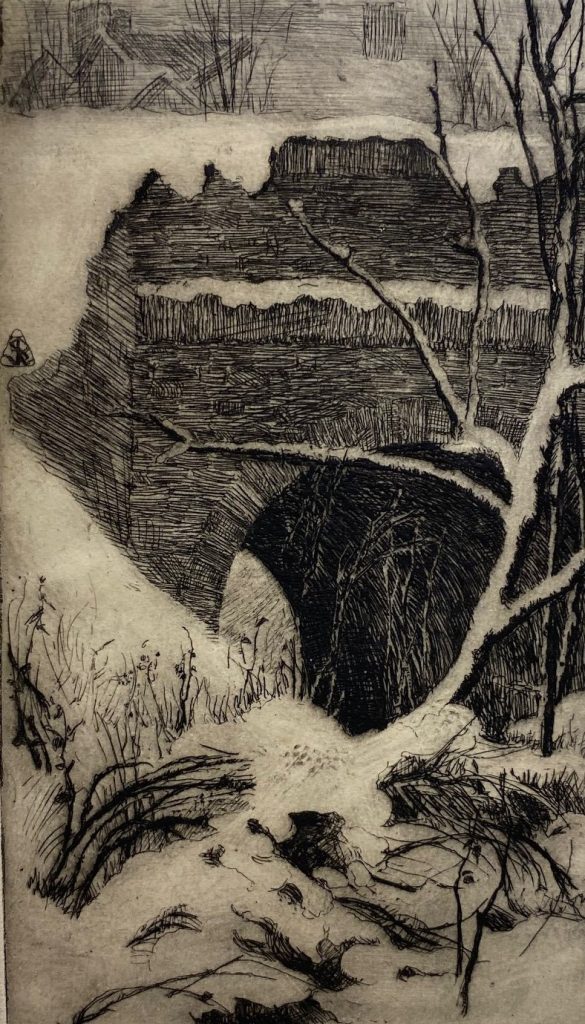

A visit to Lincoln Park in Winter produced this etching:

By Ralph Fletcher Seymour

Printed by Henry Rosenthal, Sr.

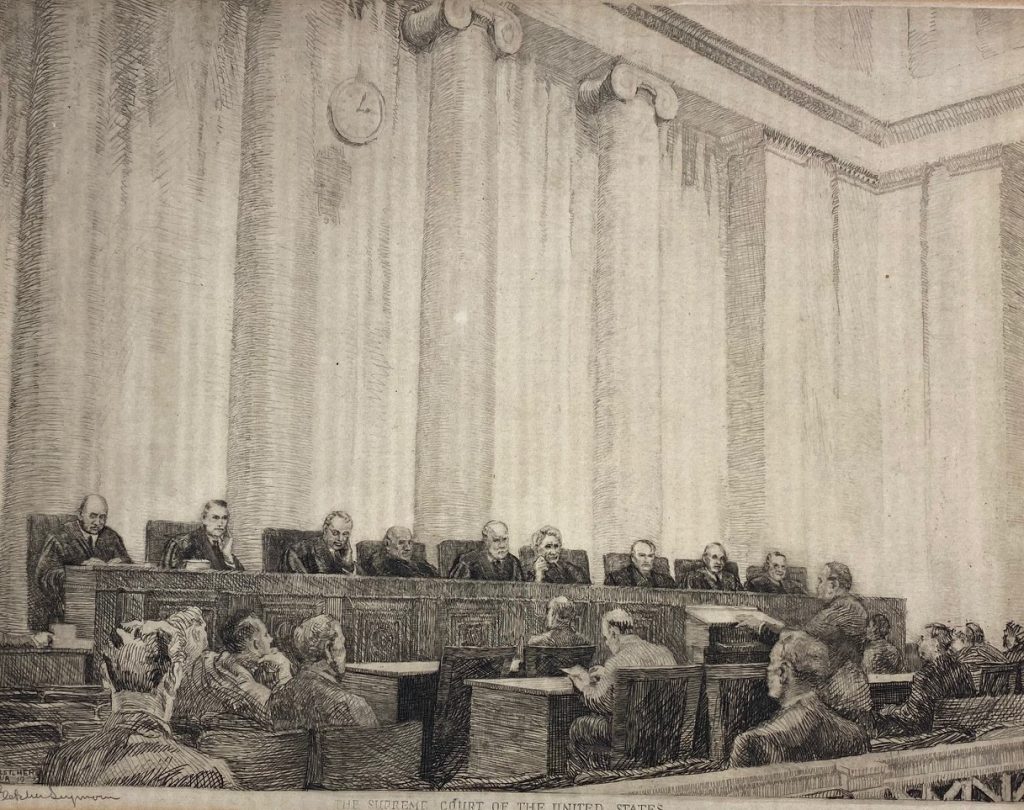

In the 1930’s there was a major confrontation between President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the Supreme Court. The Court was part of many news stories and also a subject of one of Seymour’s etchings.

By Ralph Fletcher Seymour

(This is a large etching for Seymour – 13 3/4″ by 17 3/4″. His use of space in the Chamber above the Court highlights the importance of this body of government.)

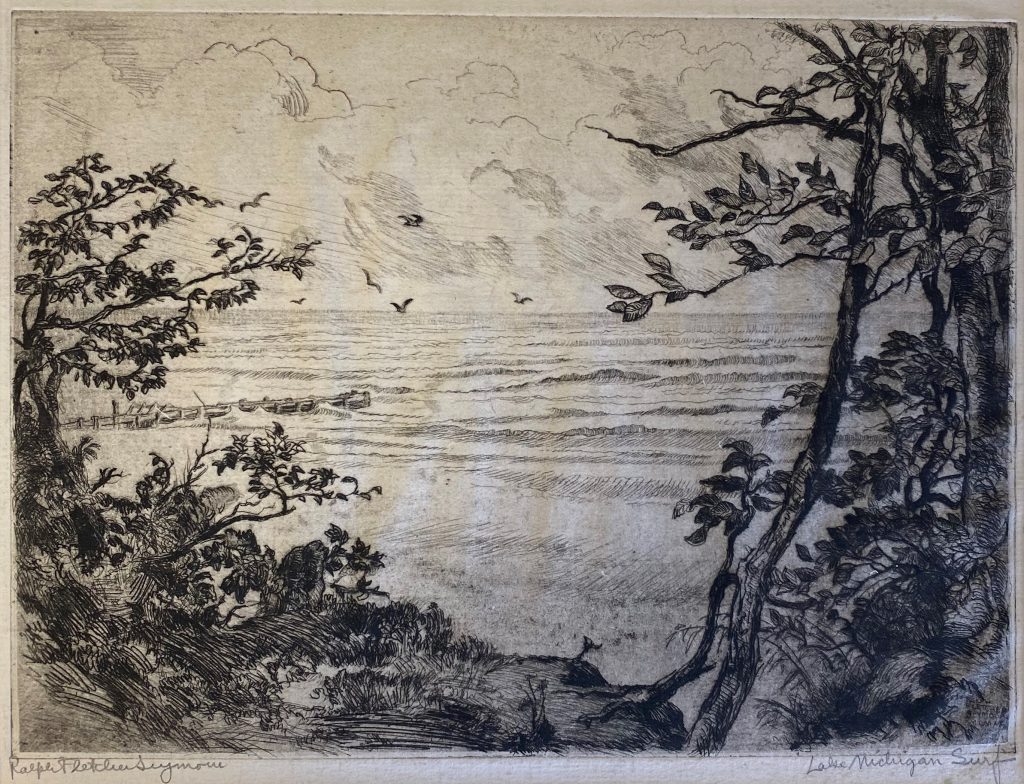

Although Seymour worked in the city of Chicago for his entire career, he decided to live in the “country.” He was one of the first non-farmers to buy land in an unincorporated area by the name of Ravinia. (now Highland Park) Of course, today Ravinia is the home of a Summer music festival. Seymour’s house was just a few blocks from Lake Michigan. He and his family loved to take walks. Undoubtedly, the scene below of “Lake Michigan Surf” was the view of the Lake near where he lived.

By Ralph Fletcher Seymour

A visit to the neighboring town of Glencoe, Illinois served as impetus for this etching:

By Ralph Fletcher Seymour

(A print of this etching is also in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D. C. )

Like many Chicagoans of his era, Seymour was fascinated by the American Indians of the the Southwest. As mentioned above, one of his “Clubs” and a source or much of his entertainment was the “Cliff Dwellers.” Despite the fact that almost none of the members had ever been “West” or had ever seen an American Indian, the name sounded rather exotic and since the meeting rooms were well above street level, the name stuck.

Seymour’s account of the first real visit of Pueblo Indians to the Cliff Dwellers meeting rooms is a great story. Suffice it to say that the 20 plus Pueblo Indians in attendance had great appetites and they could dance. Cliff Dweller members wound up standing on tables to give them room!

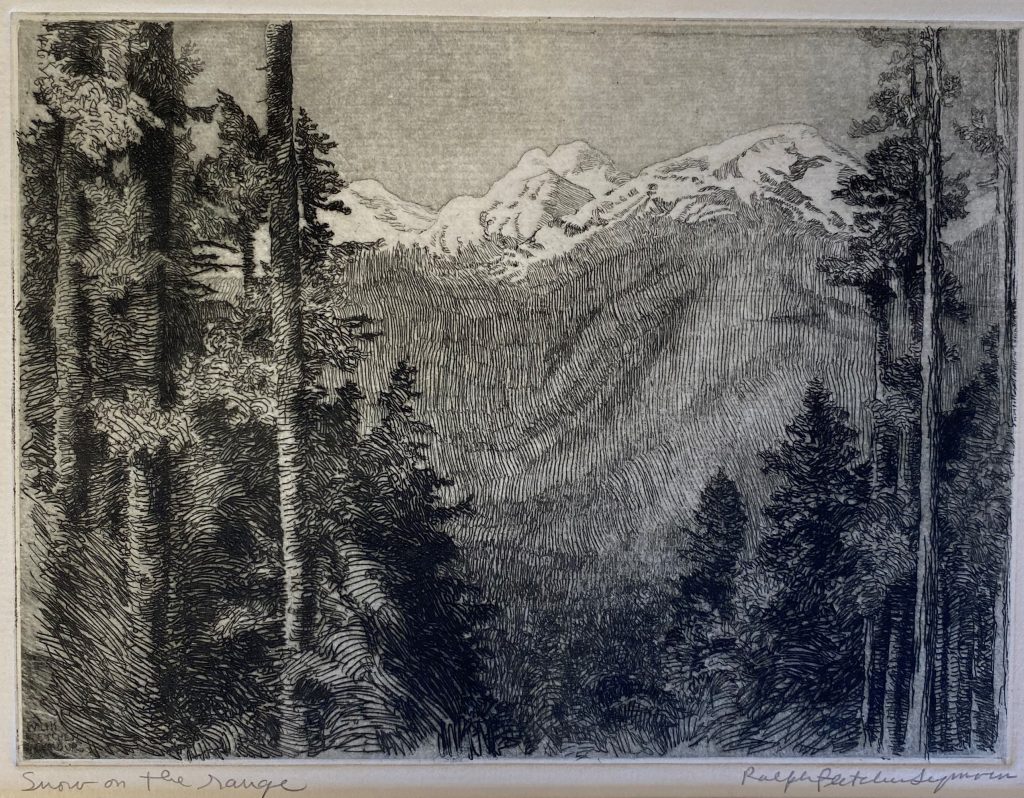

Seymour made numerous visits to New Mexico and to the Mayan and Inca ruins further South. This etching captures some of the beauty of Northern New Mexico.

By Ralph Fletcher Seymour

Spectacular scence of the mountains in Northern New Mexico

Seymour continued publishing books and producing etchings well into his 80’s. He also continued to enjoy his “clubs” and the company of his many friends. On January 1, 1966 after celebrating at a New Year’s Eve party, he decided he would like to walk home. On the way, he was struck by a car and killed instantly. He was 89.

Jim – Your blog gets more and more awesome!

Reed

Thank you for your kind words. I am glad you like it. It is also more and more fun to write the blog posts.

All the best, Jim

(Reed Isbell is the daughter-in-law of Morris Henry Hobbs and the author of his catalogue raisonne.)

A fine article. Thank you. I have at hand a copy of the second edition of L. Frank Baum’s book, FATHER GOOSE HIS BOOK, 1899. Although illustrated by W. W. Denslow (preceding their partnership on THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ), the text here was hand-lettered by Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

Mr. Seymour named his business The Alderbrink Press, although “Why?” is not answered in his autobiography, nor have I been able to find somebody who knows why he selected that title. Do you know?

One of the bookplates Seymour designed was for the Lake Zurich Golf Club, to which RFS belonged. The Club has a small golf course, and a smaller membership, and a handsome bookplate. Seymour also painted scenes in their Club House.

Mr. Seymour was headed toward his handsome log cabin home from the Blackberry Inn, along the roadway where there was no sidewalk, when he was killed by a motorist. The Inn was 10 miles west of Batavia, in unincorporated Kane County.

Thomas

Thanks. I am glad you enjoyed the article.

Your information about RFS adds significantly to the piece. I would love to see your copy of “Father Goose His Book.” Seymour mentions the negotiations he had with Denslow and Baum on payment for lettering the book in his autobiography. He says he was paid $50 and free lunches prepared by Denslow’s wife.

The only Alderbrink Press book I own is “The Voices of the Dunes and Other Etchings” by Earl Reed. Reed was one of the founders of the Chicago Society of Etchers. I do not know where Seymour came up with the name “Alderbrink Press.” He probably made it up with the hope that people would be trying to figure it out many years after his death. I was aware of his connection to the Lake Zurich Golf Club. I have seen photographs of the bookplate he designed for the Club as well as some of the etchings that hang on their walls. I did not include them in my article since I only use images of prints that I own.

Thank you also for the explanation of how and where he was hit by the car. Somehow I had the idea that he was at the Lake Zurich Golf Club that New Years Eve, but the location of the accident did not fit. Now I know he was at the Blackberry Inn.

Seymour was quite a personality. I enjoy his artwork and enjoyed writing the story. Thanks again.

Dear Mr Rosenthal

Tom Joyce recommended this excellent article to me. I am the editor of the Caxtonian, the journal of the Caxton Club, and would be very interested in publishing a version of this essay there.

If you are interested, please write to me at my e.mail address.

Thank you.

Michael

I am glad you enjoyed the article. You are welcome to use all or part of the article for the Caxtonian. Seymour was a great supporter of your organization. I will send you an email.

Jim

Hello, Mr. Rosenthal. I picked up this etching at a local estate sale. Might you be able to tell if it is one of Ralph Fletcher Seymour’s? It says Seymour in the lower left corner and it appears to be consistent with his signature but doesn’t have is first and middle names. I can email the photo to you.

Sure. I would be glad to take a look at your etching. Send pictures of the etching to jimrosenthal5757@aol.com. Please include a close up of the signature. I might be able to help – but no guarantees.

Mr. Rosenthal:

I happened upon your blog and have read several of your fascinating stories. I authored CHICAGO ARTIST COLONIES two years ago and it would have benefited mightily from some of the information contained in your blog stories, in particular your stories on the the Tree Studios, Fine Arts Building and Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

Mr. Seymour, in particular, intrigues me. For decades that multi-talented gentleman was at the center of a remarkable group of interesting and accomplished artists from every field, a veritable who’s who of Midwestern culture, and other prominent Chicagoans outside the arts. I have begun research on this coterie of friends as a subject for a new book and would love to locate Mr. Seymour’s papers. They are not to be found in any of the usual suspect institutions, several of which hold the private papers of his contemporaries, i.e. Néwberry, Chicago History Museum, AIC, Univ. of Chicago. Surely his Aldebrink Press archives and his correspondence must have been somewhat voluminous. Perhaps they remain moldering in crates stuffed up in in the attic of a descendant.

Thanks for your interesting blog and any additional information you can share on Mr. Seymour.

Keith

I am glad you liked some of my stories. I enjoy writing them – knowing that someone reads them and finds them interesting is a huge bonus.

Most of the information I have on Seymour is from his autobiography – “Some Went This Way.” The letters I quoted were from the James Swann/ Bertha Jaques archives at the Cedar Rapids Museum Of Art. There may be more letters from or about Seymour in the Archives.

Seymour was an active artist, but his primary business was book publishing. It could be that fine book collectors (like those in the Caxton Club) may have more information on the whereabouts of his papers.

I just ordered your book and am looking forward to reading it. I plan on writing more articles on individuals in the Chicago art scene and I am sure it will be a helpful resource.

I met Mr. Seymour when I was in high school, back in 1963-64. He was very patient with a young person with an interest in the arts. A few years before I met him, he bought a patch of woods west of Elburn, IL. He cut down some trees, brought in a sawmill, and built a house with materials from the site. The fireplace was made of rocks from the woods and clay from the creek bank. He was proud of his house, and enjoyed talking about its construction.

I was talking with Mr. Seymour one day when he picked up a letter that he had just received from a friend. “He sends me these letters,” Mr. Seymour said, “and I can never figure out what he’s talking about. Can you make any sense of this?” The letter was fragmentary, incoherent, and practically indecipherable. The writer was Ezra Pound.

I have other memories of my conversations with Mr. Seymour. Now, in my own 75th year, I think of him fondly.

Thank you so much for this account about your contact with Ralph Fletcher Seymour. Your experience confirms what so many others have said about him. He loved being around people, good conversation and a good story. I wonder if he really could not understand Ezra Pound or if he used the letters to amuse and engage his young friend. In either case, this too is a good story.

Seymour really was born in Milan, Illinois. All his census and travel records say Illinois, and as his father Otto was a traveling salesman, they moved around. They settled with the Fletchers in LaPorte due to Otto Seymour’s frequent absences. Very interesting article!

Thank you for this information. I will edit the article accordingly. I guess that is the advantage of a blog over a book. With a book you have to live with your errors forever!

Hello Jim,

I have been a fan of RFS for many years, but not for anything that you mention. He was an Artist in Residence at Knox College in 1936-7, and did a number of etchings for Knox. I own two, one that is fairly common of “Old Main” Knox College, and another that is absolutely rare, the “East door of Old Main”. He also is attributed with the design of the current Knox College Seal.

As a Knox Alum, I have always had a great deal of respect and love for him, and it has only grown over the years. Thank you for this wonderful bio of him.

Mr. Rosenthal, last year in 2022, Lincoln Elementary School in La Porte, Indiana donated 8 paintings by RFS to our La Porte County Historical Society Museum. They were the original models of the murals painted for the Lincoln Room at the La Salle Hotel in Chicago. Seymour had donated the models to his alma mater, La Porte High School, in 1957. We have them on display in our museum this summer. I had never heard of Ralph Fletcher Seymour and have been researching him for several months. I find his story fascinating and have found so many interesting facts about his life in La Porte, Chicago, and beyond. My article will appear in the La Porte County Herald-Dispatch this month, June 2023. Thank you for sharing your detailed information. Bruce R. Johnson, LaPorte County Historian

Thank you for letting us know about the exhibit on Ralph Fletcher Seymour in the La Porte County Historical Society Museum. I am sure your exhibit will be well received by your patrons. Hopefully, my article will help to provide some background information on this interesting and very talented man.